While the family lived at Park Road Michael attended the nearby Christchurch Infants School, a scant minute's walk away in Montpellier. The Hurd's then moved house, firstly to 'Brantwood', a substantial property in Reservoir Road and then again to a detached home in Southfield Road, both homes in neatly prosperous locations on the south-eastern edge of Gloucester. The latter address was conveniently placed for both Calton Road Junior School and The Crypt Grammar School, the next steps on Michael's educational path. The quiet residential area was well served by buses and only half an hour's walk from the city centre.

|

Southfield Road, Gloucester, 2006

|

Firm in business he may have been but Michael's father was certainly a shrewd investor of his income. Property was the fashion of the day and eventually the family would have, in addition to Southfield Road, an interest in some eight or nine small houses in Gloucester. This established a moderate legacy that provided Michael with his share of a useful 'cushion' when contemplating a later career move into freelance work.

Those who lay store by the influence or otherwise of family life may note that there was no more or less emphasis on music and the arts in the Hurd household than would have been the case in any other of similar background at this time.

|

But there was of course a wireless and a gramophone, even if the latter was a pretty basic model which in later years lived under Michael's bed in a suitcase, as if he were somehow suspicious or ashamed of the technology. Perhaps the shame was the Marlene Dietrich records that spiced his diet of Dvorak and Italian opera. |

More importantly, the main living room housed an "untuned" upright piano on which the young composer began his exploration of keys, harmonies and the sheer pleasure of playing. Michael fondly recalled picking out "Tiptoe Through the Tulips" and other popular tunes of the day "as soon as I could walk." Later he began to get to grips with basic music notation, with the help of a friend of one of his half-sisters. Music and reading developed together in the young boy, whose later passion for English lyric poetry is unlikely to have been nurtured in a home without any books or easy to access to a good public library.

|

After Christchurch Infants and Calton Road Juniors, where the weekly singing lesson was all the music there ever was, Michael went in September 1940 to The Crypt, the older of the two grammar schools for boys in the city. In the previous year, the first of the war, the premises had been shared by an evacuee school from Birmingham, but that arrangement had ended in the spring of 1940 and by the time Michael took his place, school life had settled back into what passed for a normal routine during those difficult years.

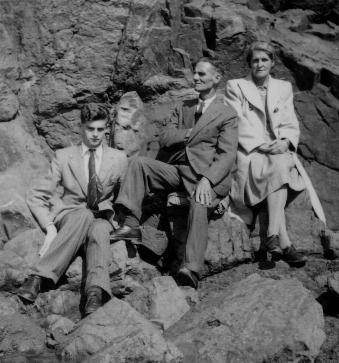

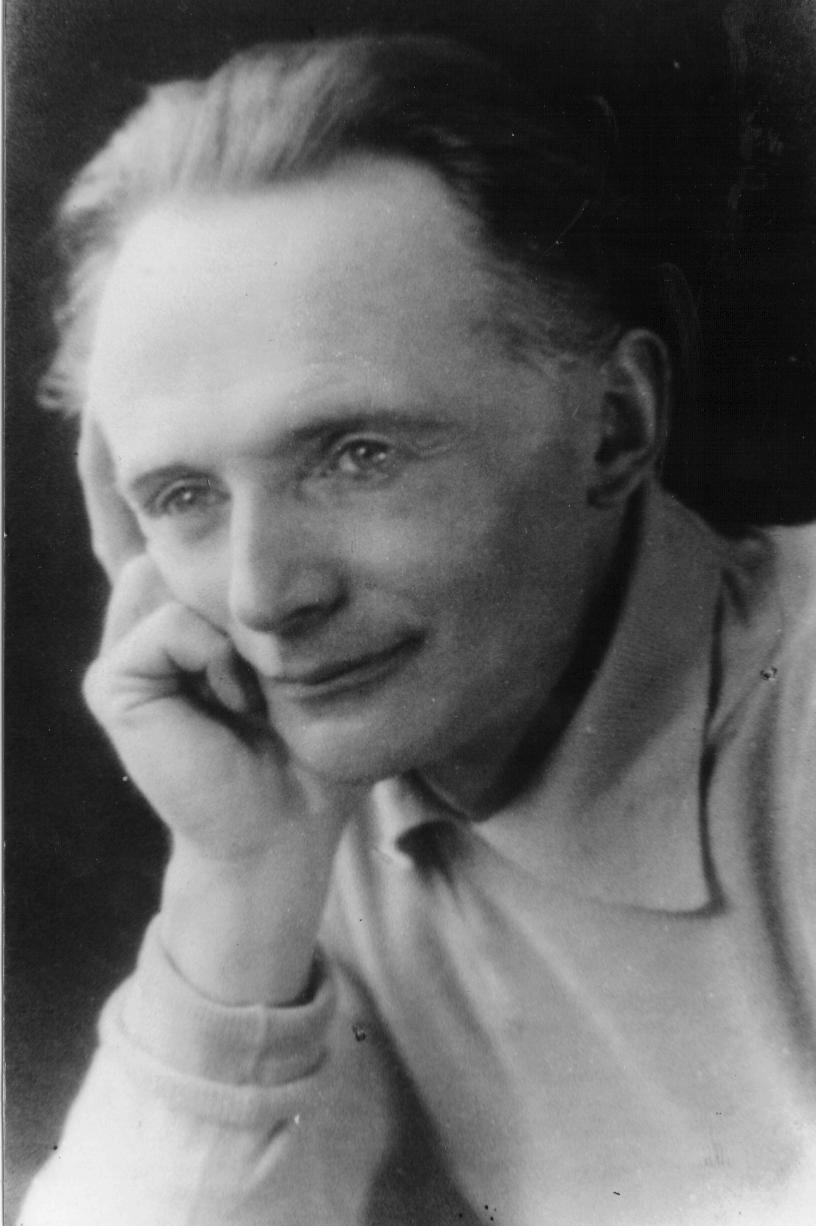

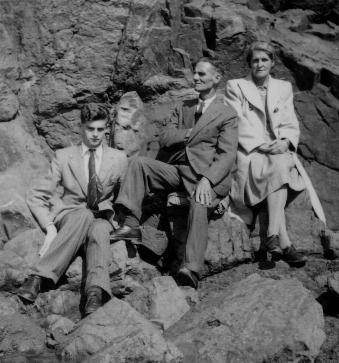

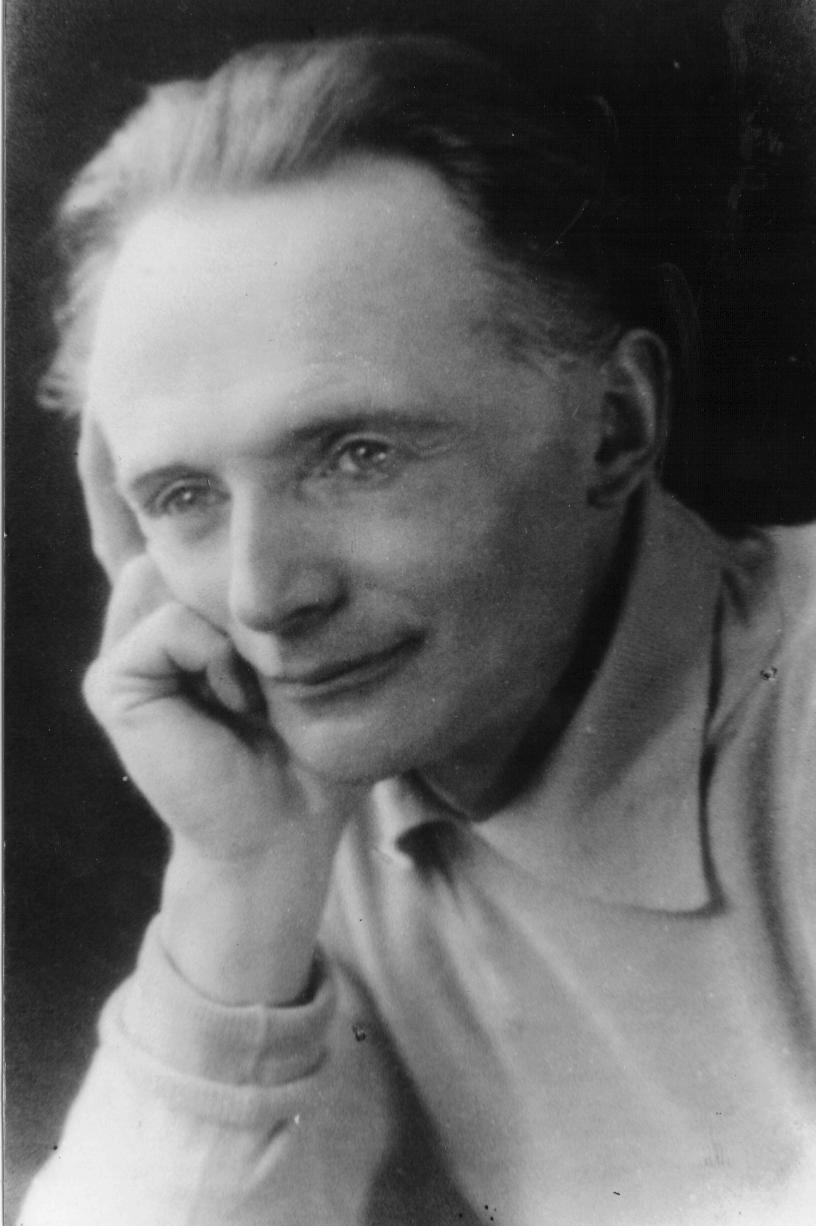

As might be surmised from the standard of their family homes, the Hurds were reasonably well-to-do by the generally straitened conditions of the time. A photograph of a family holiday, at Bude in Cornwall, shows a formally-dressed if rather self-conscious trio. Other portrait photographs, of which there are many, indicate that Michael, here with the usual awkwardness of mid-teens, inherited and cultivated his father's apparent weakness for a striking pose.

|

|

A self-confessed "urge" to compose music began about now, after hearing a wireless broadcast of Puccini's Madam Butterfly. "I had no idea what it was, or what it was about, but I fell in love with the sound and wanted to imitate it." Numbered among a substantial collection of recorded music left at his death were no less than four different versions of this work, perhaps indicative of its lasting effect.

During his time at The Crypt Michael's speed on the uptake and originality of thought underpinned a thorough if unexciting academic grounding, with the addition of stimulating a profitable use of the central library in Brunswick Road to supplement his reading. He also furthered his own musical studies. Listening to records, following scores and picking out themes and chords on the piano were the only, yet immensely practical, ways to absorb and learn.

Indeed, it was in the music section of Gloucester Public Library that as a fifteen-year old he made a significant discovery that would colour a greater part of his early working life - the music of Rutland Boughton. He borrowed the vocal scores of The Immortal Hour and Bethlehem, in all likelihood picking out the main themes on the keyboard at home with his highly individual fingering style. Thus the flame was lit for a lifelong interest in and championing of that engagingly eccentric composer.

|

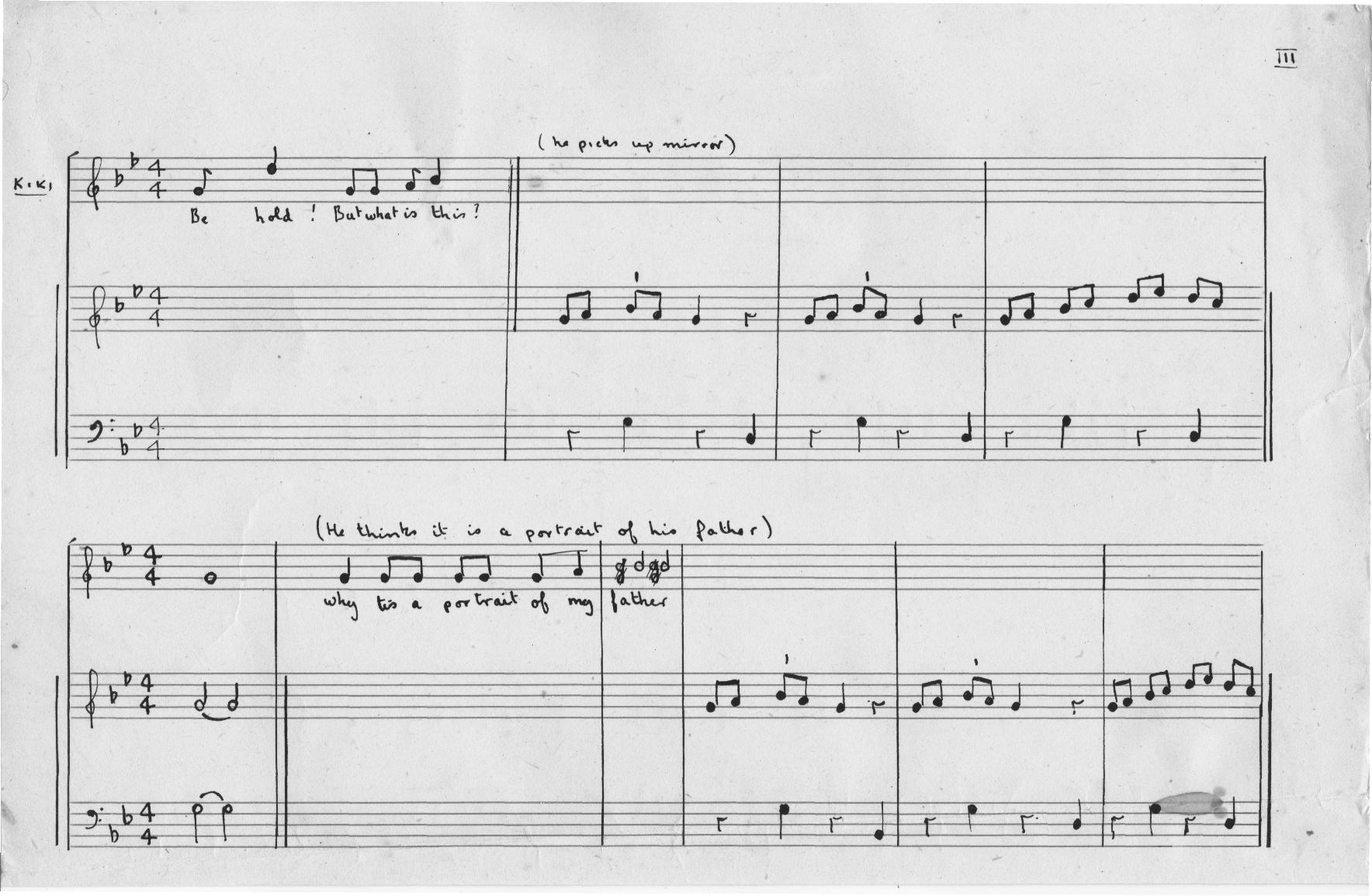

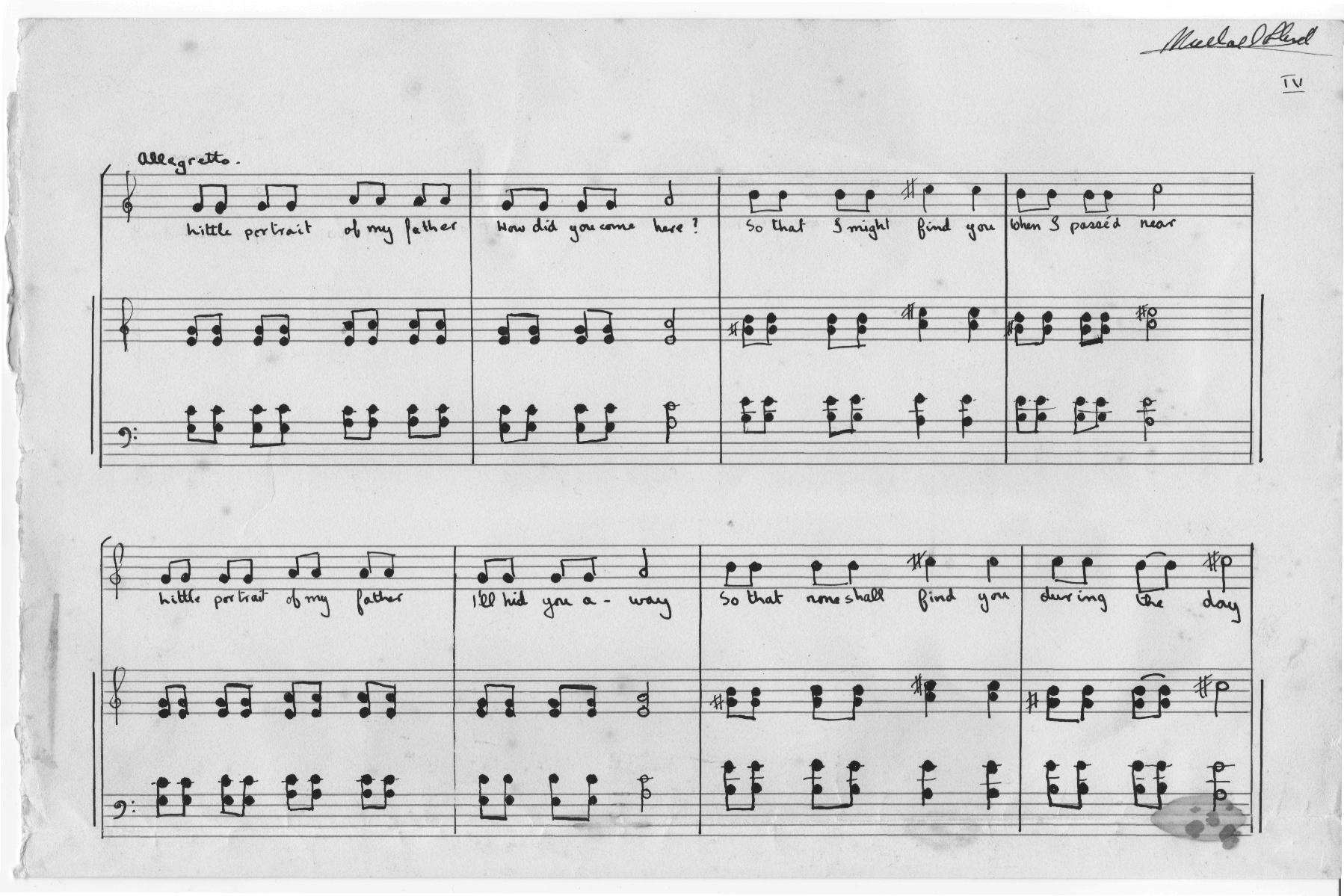

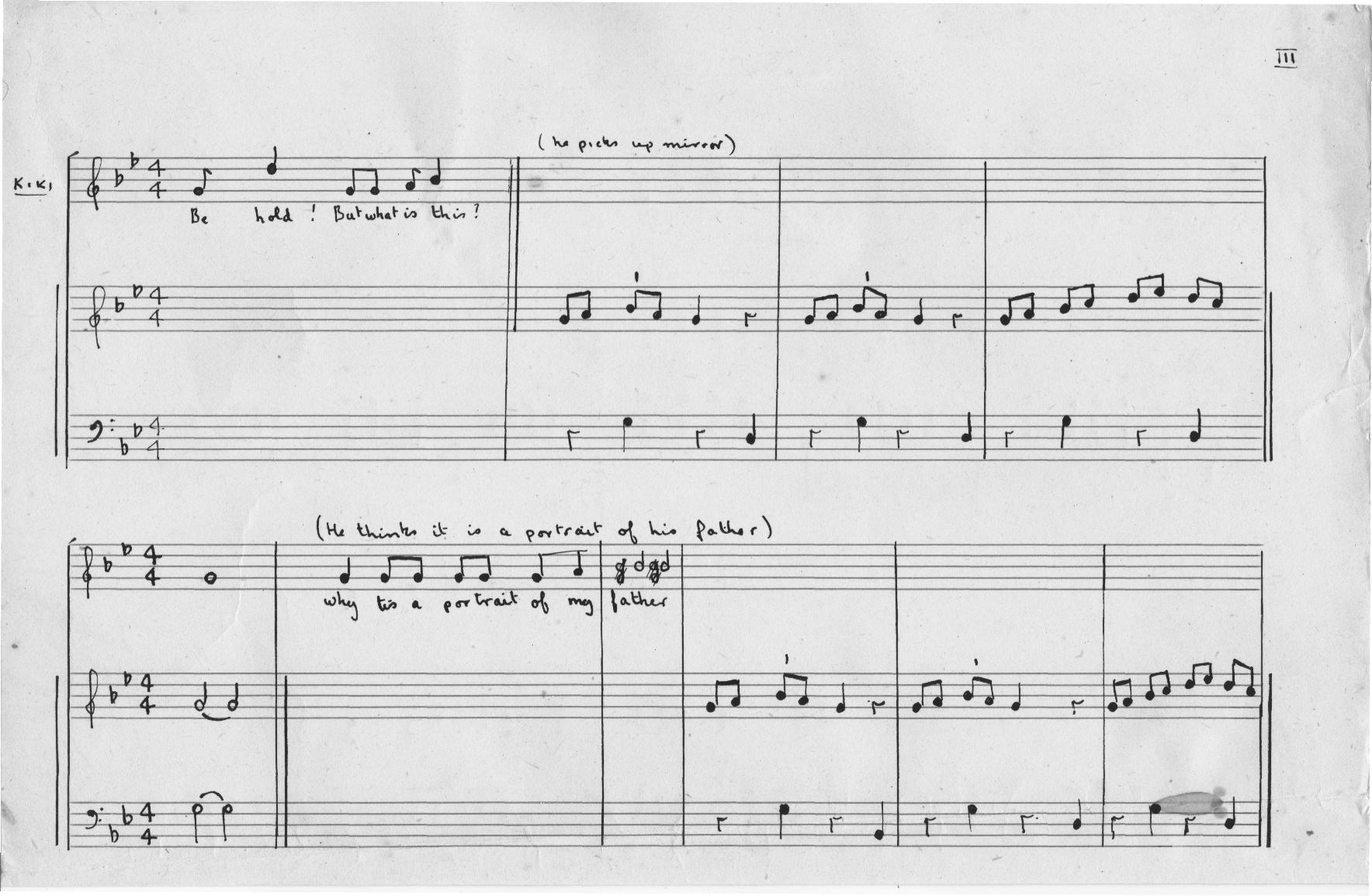

Part of the earliest surviving score |

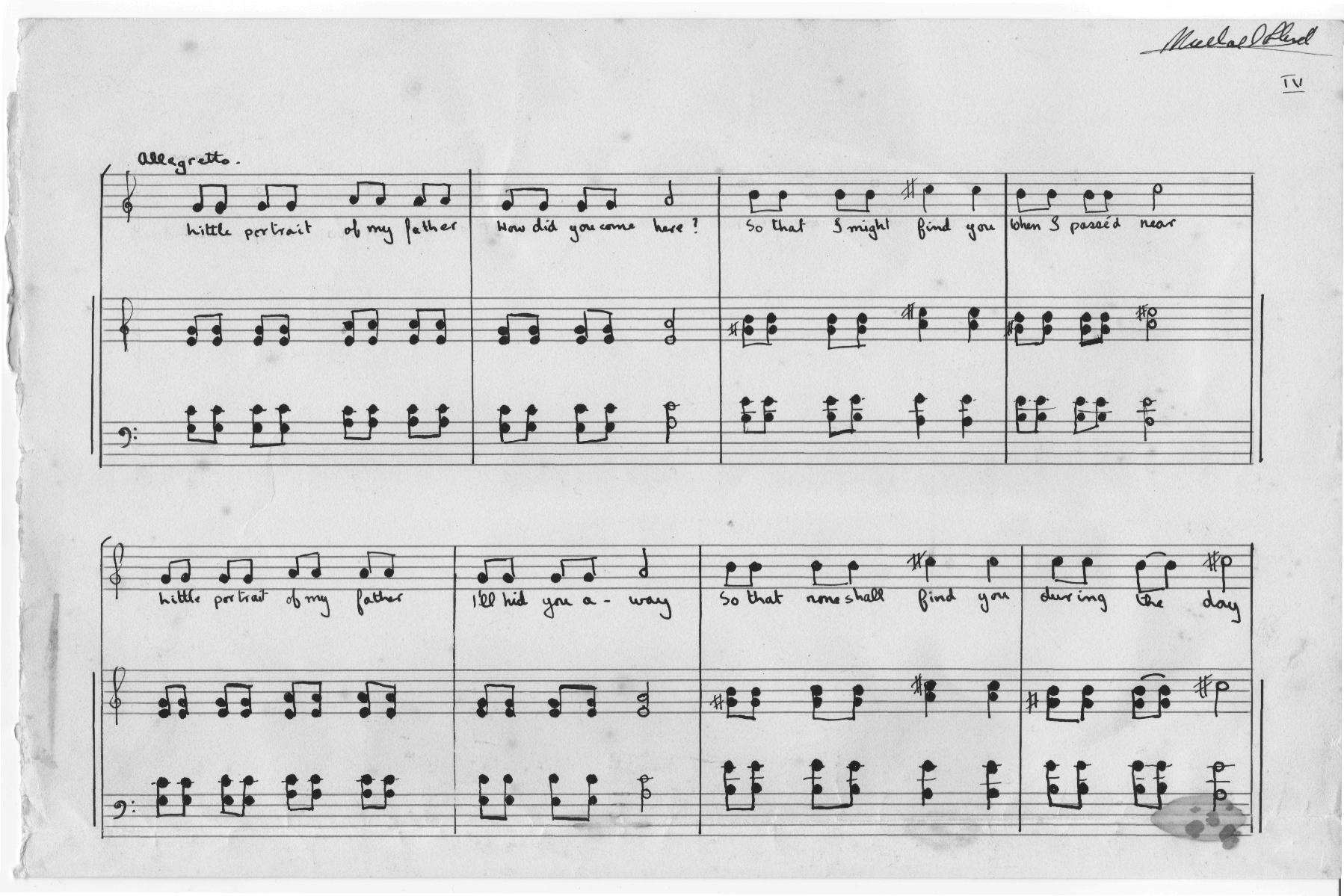

A juvenile 'opera' fragment survives from 1942, when Michael was just fourteen, featuring the quasi-Gilbertian characters Kiki-Tsum and Lili-Tsum. The script is neat and the musical matter may be influenced by Sullivan. The fair copy layout is highly professional for the age of the artist, but the libretto is almost a definition of twee and the adult composer has added a later and succinctly pencilled critique - "Dreadful !!". Derivative the piece may be, but Michael's admiration for and love of the Savoy tradition was to last him through his life. He was justifiably proud to have conducted the entire Gilbert and Sullivan canon in Petersfield.

Michael's developing passion for and interest in music eventually led to his deciding to take it as a subject at Higher School Certificate [the equivalent of A-Level], a decision which he later claimed to have been to the consternation of the teaching staff. "No-one else had attempted this in its 400-year history!" The music master, Harry Dawes, apparently at a loss, produced an ancient copy of Sir John Stainer's "Harmony" and Michael got a few minutes each week in a lunch hour to work his way through it.

"The exercises were all based on single and double chants, so the idea of a quaver was exotic and a semi-quaver beyond comprehension!" But, stodgy as it must have seemed, Michael ploughed doggedly through the work as if aware that, poor as it was, this "tuition" was better than nothing. |

A contemporary recalls Michael at this time as having apparently more maturity than those around him, with a precocious disdain for the commonplace (eg walking to school since "My cycling days are over"). While Michael had discovered Puccini and Richard Strauss, not then as popular as they are now, others were wrestling with rather more mainstream music.

Invited to take part in a music circle, where members played selections on discs and explained their enthusiasm for the chosen piece, Michael produced a sample of Italian opera (perhaps Mascagni, another favourite) and declared that he had nothing whatever to say to the group about the music since they, the group, were not worthy of it. A considerable dollop of boyish charm would have been needed to rescue this faux pas, but rescued it apparently was. |

© Gerald Pates, Gloucester |

|

This precociousness may have led to a degree of isolation but Michael happily joined bus excursions to the nearby Cheltenham Town Hall, where the CBSO and other orchestras were regular and welcome visitors, even in those disturbed times. An ability to listen, analyse and absorb was, he later acknowledged, a key aspect of his development as a student of music and musicians. Another regular Cheltenham lure was the Daffodil Cinema near Suffolk Square, where Cheltenham Film Society fostered a lively interest in foreign language films.

That he had a degree of confidence in his own tastes and interests was increasingly apparent. An incident in an English lesson is germane; challenged for inattention, the aspiring artist is recalled as responding that he was "just composing his new love-duet". On games afternoons, in those far off days before compulsory PE, he would much more likely be found sitting somewhere quiet with a volume of Baudelaire than anywhere near a bouncing ball of any kind.

This early love of English and translated poetry, nurtured through schooling and his own studies, never left him and was a source for a great deal of his professional work and private pleasure. Over the years he developed a substantial personal library of verse from all traditions and eras, with lyric setting a principal inspiration in much of his music and broadcasting.

|

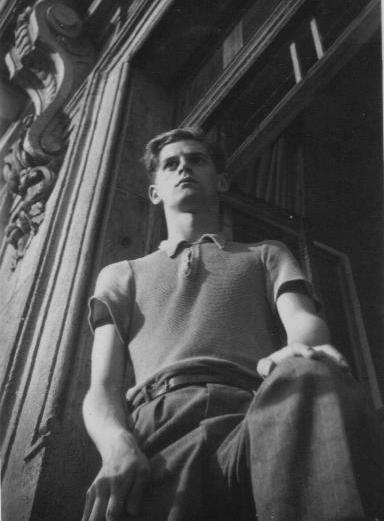

He played an active role in the school's burgeoning cultural life, taking part in many music and theatrical events, including the writing of incidental music for a scaled-down production of Hamlet in 1946. He was also partly responsible for the abridgement. No school staff were involved in this venture, in which Michael played Ophelia, Geoffrey Peck Gertrude and James Roose-Evans the Prince.

After maintaining contact at university, in adult life Ophelia and the Prince would collaborate again, on Roose-Evans's sympathetic and widely successful adaptation of Laurie Lee's Cider With Rosie, for which Michael wrote the music.

|

James Roose-Evans (Hamlet) & Michael Hurd (Ophelia)

|

|

As a composer of songs and a later acknowledged expert on other setters, Michael Hurd began work early in this field. While still at school, in addition to work for the Hamlet production, he wrote a setting, now lost, of 'Fear No More the Heat of the Sun' from Cymbeline, which a contemporary has described as being 'daringly chromatic'. He also set Shelley and Thomas Lovell Beddoes, this last an early example of his taste for ferreting out the obscure and macabre. Beddoes was a Pembroke College man, so is it only a coincidence that Michael later chose to apply there ?

|

"an adequate if unstartling technique" |

Learning to play the piano by experience led to an adequate if unstartling technique, but by the time he left The Crypt he could cope with early Beethoven sonatas. There was certainly a performance of both the first movement of the Appassionata and a Mozart sonata at one of the school's music society concerts.

In all, his school days show evidence of an instinctive grasp of anything to do with music and poetic language, an understanding that was to inform and illuminate much of his working life. When the time came to opt for subjects in the senior forms however, Michael initially entered the Science Sixth with physic and chemistry in mind. This lasted for less than a term and he switched to the Arts.

|

Michael may have been outgrowing the musical confines of his school, but he was certainly set on making the subject a large part of his life. He turned for advice to a local composer and music lecturer, Alexander Brent-Smith. Brent-Smith, who had taught Peter Pears at Lancing College, had a considerable reputation in the region - his Sullivanesque operetta The Captain's Parrot had been well received - and such a forward approach indicates some of Michael's confidence. There must have been a significant body of work to be perused by this time, since Brent-Smith recognised at least the young man's enthusiasm and talent and encouraged him to make music his career.

|

NATIONAL SERVICE

In the autumn of 1947 Michael Hurd, like every healthy young man of his generation, interrupted his education and reported for National Service. This was to begin at Gloucester's Reservoir Barracks, on the slopes of Robinswood Hill and thus only a few minutes walk from his family home.

Also in common with others from his background, Michael experienced a degree of culture shock as the army took him in - the fact that the boy in the next bed couldn't read or write a letter to his girlfriend being a typical example. After preliminary assessment and what he described himself as a "series of happy accidents" he was assigned to the Intelligence Corps and undertook his initial training at Maresfield in Sussex.

There followed a posting that would have warmed the heart of any aspiring musician and lover of the arts; to Vienna, still then under the control of the four victorious powers.

Despite the post-war privations still holding sway, as strikingly depicted in the film The Third Man, that most romantic city's cafes, bookshops, theatres and above all the opera provided just as valuable an education as the deferred entry into Oxford University. The duties with the Intelligence corps were in connection with the chaos of the refugee problem but Michael's role involved little more than clerical work. Whatever the tasks assigned or his attitude to them, he played the game enough to end his time in the army at the relatively lofty rank of sergeant. Despite the post-war privations still holding sway, as strikingly depicted in the film The Third Man, that most romantic city's cafes, bookshops, theatres and above all the opera provided just as valuable an education as the deferred entry into Oxford University. The duties with the Intelligence corps were in connection with the chaos of the refugee problem but Michael's role involved little more than clerical work. Whatever the tasks assigned or his attitude to them, he played the game enough to end his time in the army at the relatively lofty rank of sergeant.  Determined, however, to enjoy life to the full and falling in with a like-minded coterie, the twenty-year old flourished in Vienna, living as he did in apartment in the city rather than some remote barrack block. He returned as many did to civilian life with a markedly increased maturity in experience and outlook - which was, of course, a major aim of the whole National Service exercise.

Determined, however, to enjoy life to the full and falling in with a like-minded coterie, the twenty-year old flourished in Vienna, living as he did in apartment in the city rather than some remote barrack block. He returned as many did to civilian life with a markedly increased maturity in experience and outlook - which was, of course, a major aim of the whole National Service exercise.

In addition to fuelling an existing passion for the operas of Puccini and Korngold (with missionary zeal he bore home a vocal score of Die Tote Stadt), Michael's time in Vienna kindled an admiration for Mozart. There were also further developments in his experiments in song-setting.

|

A manuscript in the Bodleian Library, Oxford, lists Ten Songs with Piano, with settings of verse by de la Mare, Scott, Blake, Dehn and Colum. The work is variously dated Gloucester 1947, Vienna 1948 and Gloucester again 1949. He would return in later years to the writings of de la Mare and Dehn, with both of whom he had developed an affinity.

It would be only fair to record that Michael's time in Vienna was not restricted to military or cultural matters. Contemporaries at home were regaled with accounts of what appears to have been a lively social scene - again demonstrating (or simulating) a maturity beyond his apparent years or experience. But he would not have been the first or last young man to relish sharing real or imagined encounters.

|  Michael, rediscovering his old

Vienna apartment block in 1986 |

Breaks from work and high culture in Vienna included a stay in Italy, taking in Florence, Lucca and Rome during July 1949. Two postcards home are worth including here, capturing as they do the young traveller's unabashed response to the capital city. Spelling and punctuation as in the originals.

|

|

Via Ludovini, Roma

"My dear parents, It is wonderful! You know how much I love Vienna - Rome is inexpressively better. I have almost died of the beauty and lovelyness. And there is so much to buy - and not dear like England. And the people are so well dressed ! Thank God I brought my summer clothes. My room is quite nice and there are nice people here - the food is good and all quite cheap. Will write again. Wish you were here too - but you MUST come some day.

p.s. Spent today bathing in the SEA! (Meditterranean!)"

|

"Today I went round the Vatican and the Colesseum - both wonderful. But tonight I went up to the grounds of the Villa Borghese and looked out on Rome - to St Peters & the Victor Emmanuel memorial & all the little lights and domes silhouetted against the lovely night. All around were pine trees & little fountains & lights. It was so lovely that I began to weep - this is really the most lovely city on earth. There can't be anything more beautiful."

|

|

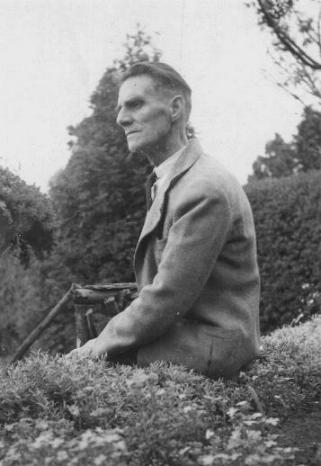

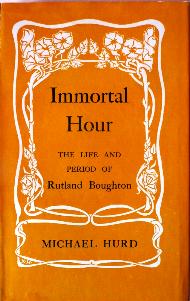

Rutland Boughton |

Having acquired this early taste for the sights and sounds of Europe (and beyond) and once established professionally, Michael became an inveterate traveller - sometimes skilfully combining work with pleasure.

In the autumn of 1949, home now from the army and nearing his twenty-first birthday, Michael posted a much more significant piece of correspondence. He had discovered that Rutland Boughton, the score of whose Immortal Hour had struck him so much at the age of fifteen, lived within relatively easy reach of Gloucester (at Kilcot, near Newent). He wrote to him, asking for advice about his own music. An encouraging reply was received and Michael, armed with examples of his work, travelled by bus and foot to meet his hero.

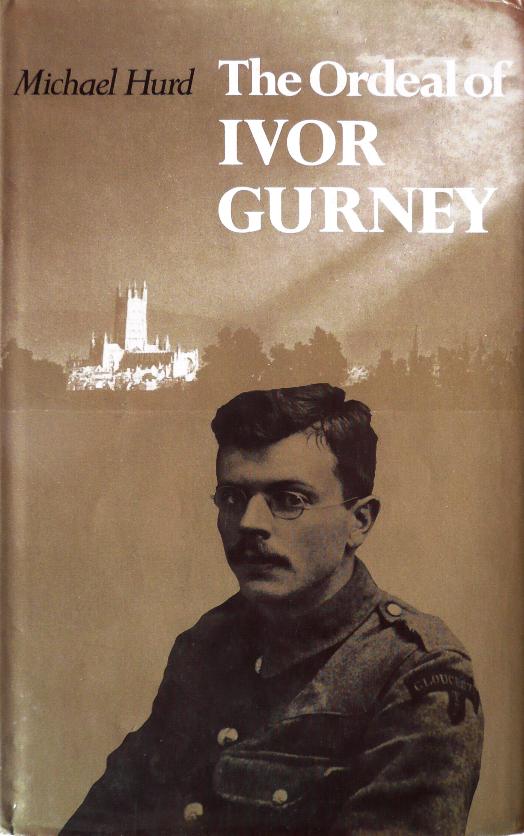

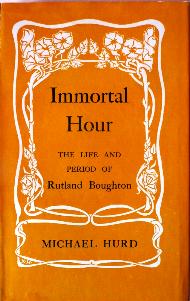

The encounter went very well and the unlikely pairing of a seventy-year old composer-philosopher and a fresh-faced enthusiast resulted in a friendship which lasted until Boughton's death in 1960. The relationship was to produce Michael's first biographical work, Immortal Hour.

|

PEMBROKE COLLEGE, OXFORD

Having deferred his entry to Oxford until the Michaelmas term of 1950, Michael had a year to fill, which he did partly by occupying a menial clerical role in the RAF Records department in Eastern Avenue, Gloucester - again, just a short walk from home. There were already school and other acquaintances up at the university, and some free time was spent there and in London, but he continued his self-education in the realms of music and literature. A friend from those days notes a slight withdrawing at this period, as if the young man was becoming more focussed on what was to become his career. Having deferred his entry to Oxford until the Michaelmas term of 1950, Michael had a year to fill, which he did partly by occupying a menial clerical role in the RAF Records department in Eastern Avenue, Gloucester - again, just a short walk from home. There were already school and other acquaintances up at the university, and some free time was spent there and in London, but he continued his self-education in the realms of music and literature. A friend from those days notes a slight withdrawing at this period, as if the young man was becoming more focussed on what was to become his career.

He had been accepted by Pembroke College to read English, naturally enough given his enthusiasm for poetic expression, but during his period in Vienna and at the Records Department he changed his mind and with the persuasive help of Alexander Brent-Smith managed to assure the university that Music was a more appropriate course of study. He also undertook a crash course in counterpoint with the county Music Adviser in order to reach the necessary standard in the Preliminary Exam. That final hurdle surmounted, Michael Hurd went up to Oxford "about as ignorant, in the academic sense, of music as anyone could be" (his own description).

|

Michael was fortunate in his main tutors through these years, they being Thomas Armstrong (later Principal of the Royal Academy of Music) and Bernard Rose (organist and tutor at Queen's College). There were also sessions with Edmund Rubbra, including a close study of J S Bach's 48 Preludes and Fugues.

Composition for his own purposes proceeded apace however, and in the summer and autumn of 1951 he was exploring the song for tenor as a main expression. |

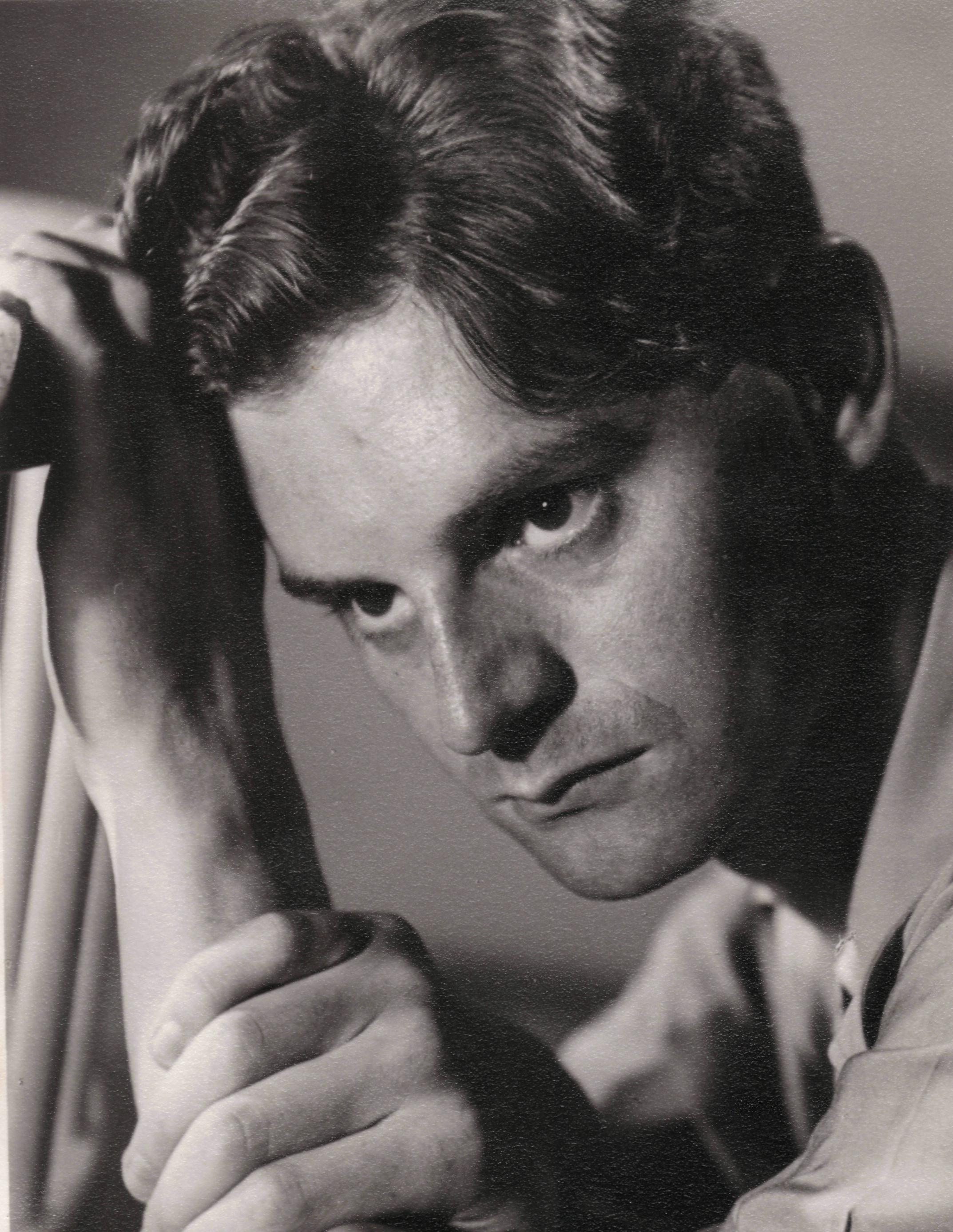

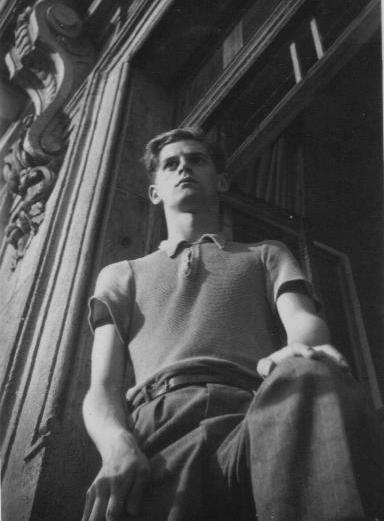

Michael on the Cherwell c1952

(Geoffrey Peck) |

In 1952 Michael provided incidental music for Neville Coghill's OUDS production of Hamlet, but it is unclear whether he recycled any of the material from his earlier school production. The important thing to note was that the initial approach to contribute came from the student, since directly seeking work and commissions was a constant theme in Michael's career. He never employed an agent.

One extant work from this period is The Night Swans, setting ten poems by Walter de la Mare for tenor and piano. Three are reworkings from the 1947-49 set but the Bodleian manuscript is finally dated 'Gloucester 1952'. Despite strenuous efforts the composer failed to find a publisher for this set - correspondence from the poet sympathises, citing the then current shortage of paper as a possible reason for rejection - but the fact that Michael never troubled to return to them in later years suggests that he realised their value as "apprentice work" but nothing more - nonetheless an essential part of the musical and professional journey.

|

He took an active role in other aspects of university life, serving as president of the Music Society and enjoying membership of both the Beaumont and Heywoode Societies, while maintaining a somewhat reclusive set of rooms in St Aldate, opposite Christ Church. The property's earlier occupants had included the Liddell family, of whom Alice found later literary fame via a rabbit hole and a looking-glass. A propensity for cultivating and developing "useful" friendships, a self-confessed theme in his career, began in earnest here. David Hughes, later to find success as an editor, critic and novelist, became a close ally. As editor of the undergraduate weekly paper Isis for a period, he arranged Michael's featuring in 1953 as one of that year's notable students, the 'Isis Idol'.

Other friendships began and cultivated in this period included the composers Geoffrey Bush and Hans Werner Henze, the latter of whom he met in London and Paris. While their friendship was undoubtedly a sincere one, the relationship with Peter Price of Tibberton Court near Gloucester was especially beneficial to Michael's work both then and in later years. Well-connected, interested in a wide range of artistic activities and having the means to indulge himself somewhat, Price was a constant source of support, both practical and moral.

|

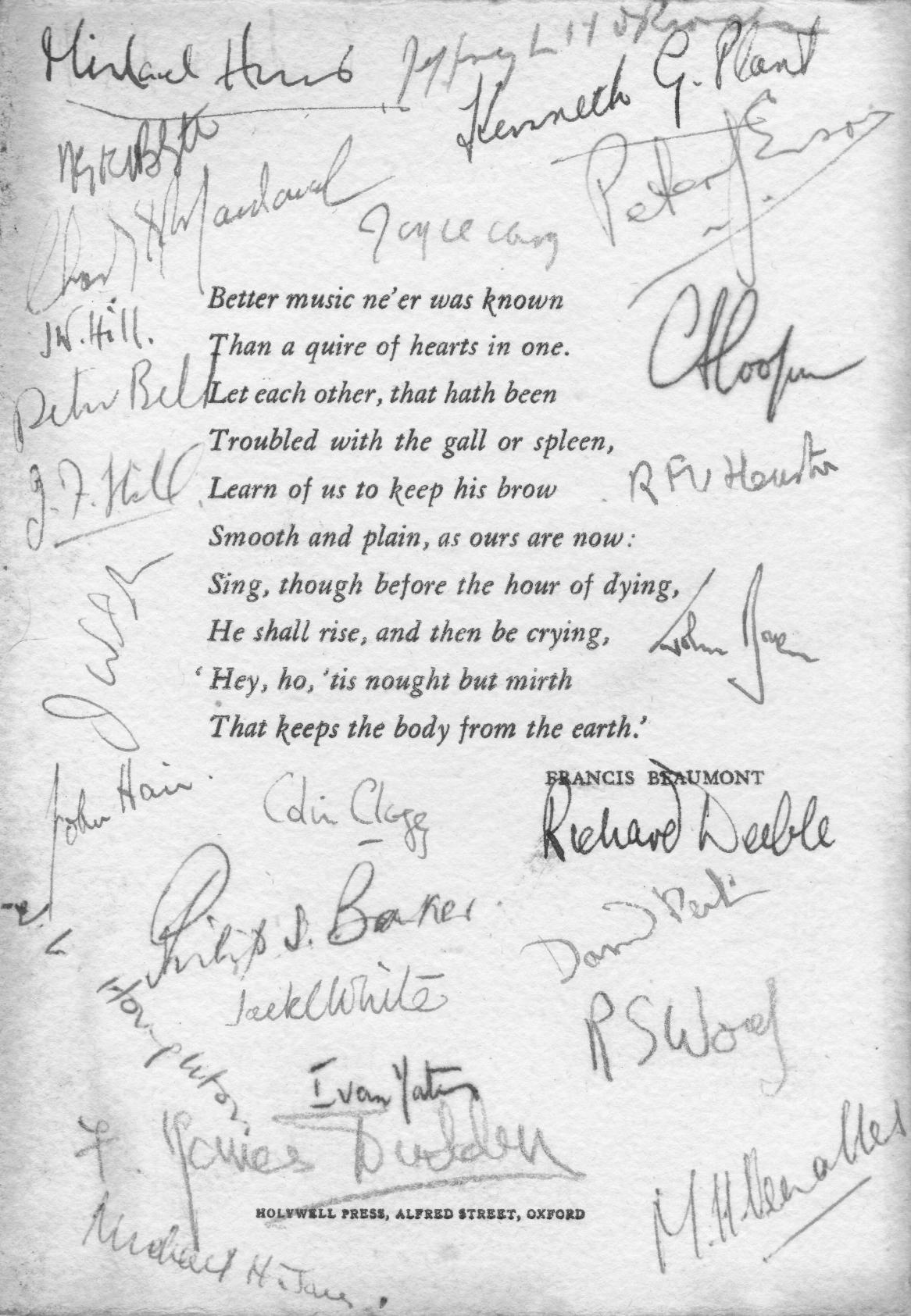

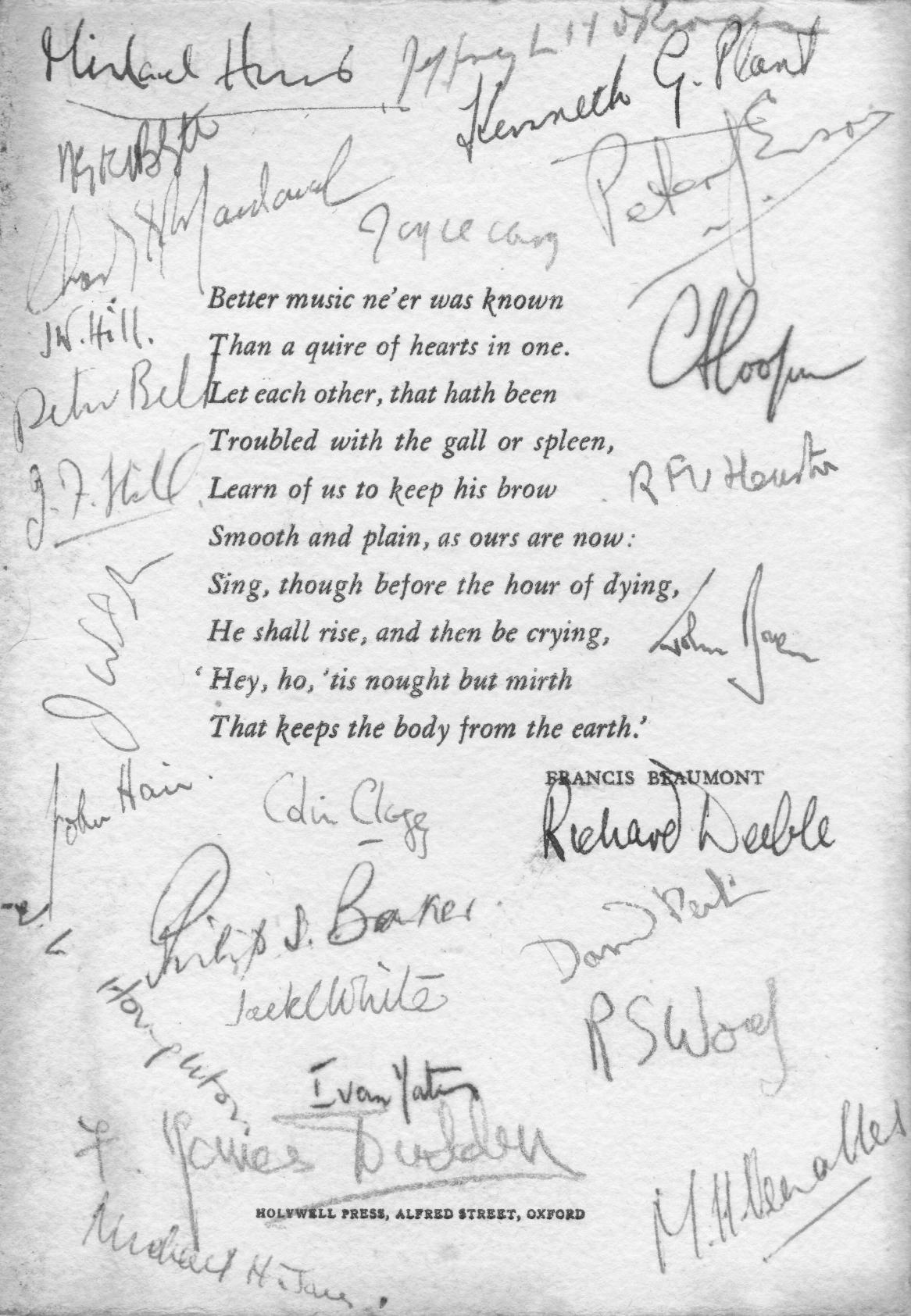

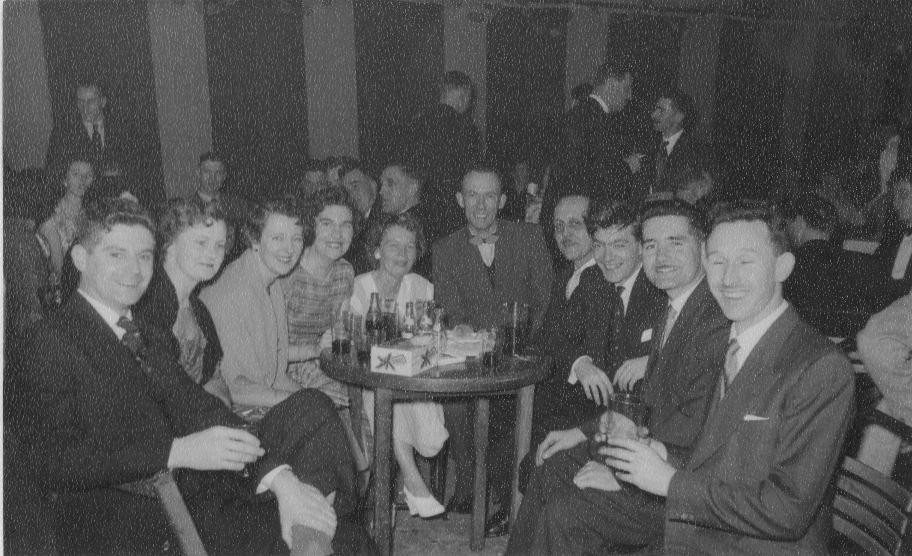

Members of the Beaumont Society

sign their 500th meeting menu card, 8 March 1952. MH top left.

|

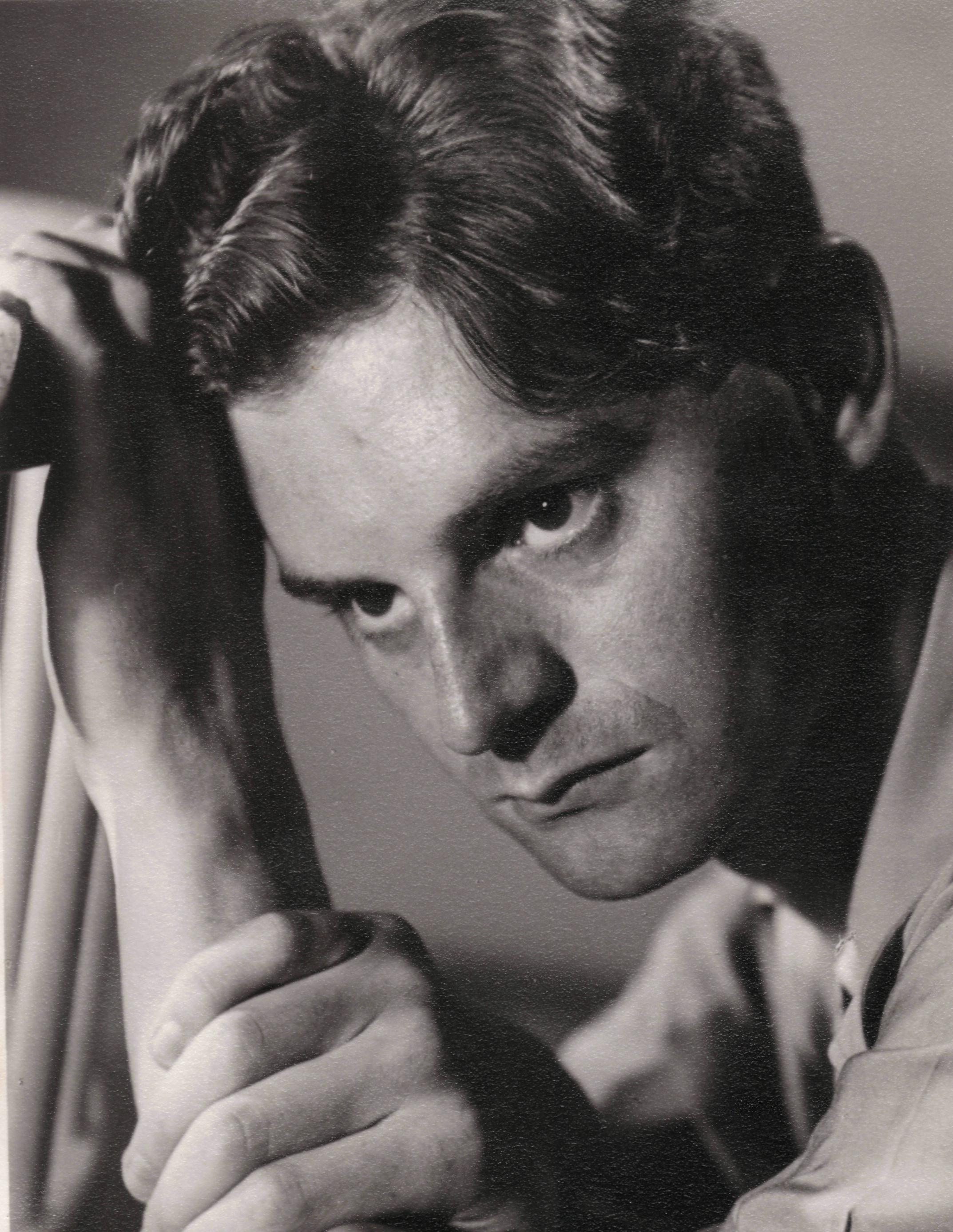

Michael in his later Oxford years

© Gerald Pates |

With regard to Oxford in general, in more mature years Michael Hurd seems to have taken on occasion a less than balanced view of his time up at the university. A private note to a fellow graduate includes

"... and teaching oneself is in fact the only way to learn anything. Apart from [Edmund] Rubbra's lectures on Bach's 48, Oxford taught me nothing - although the label has been useful in a foolish world."

Notwithstanding this lofty position, in later life he was not averse to appending "MA Oxon" to his signature where he felt it would lend weight to his argument. He also acknowledged to another friend the value of his study of Bach.

"Every note seems to be derived from the principal subject, the basic idea being made to flower in the most astonishing way. Rubbra's enthusiasm taught me to keep my mind on the main thematic point when trying to write an extended piece - even if the outcome is basically 'light music'. Everything to be said for not waffling."

|

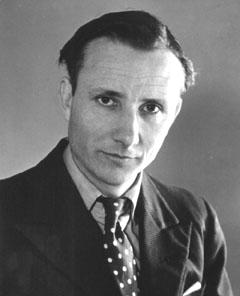

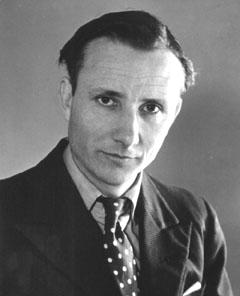

Lennox Berkeley

Michael began a highly significant relationship at this time by taking private lessons in composition from Lennox Berkeley. He had approached the senior composer for advice and assistance, having acted as page-turner when Berkeley gave a recital at Oxford with violist Forbes Watson. In both having the means and determination to arrange such encouragement Michael widened his knowledge and experience of practical musical matters, but also gained a lasting friendship with Lennox and Freda Berkeley, to whom the Missa Brevis of 1966 is dedicated.

Speaking of Berkeley's work later, Michael Hurd emphasised the attraction of music that he regarded as having elegance and economy - two epithets that have been applied several times to his own compositions. That Berkeley shared a musical affinity with Poulenc, with whom some of Michael's work has been favourably compared, wrote an opera (Nelson) on one of Michael's personal enthusiasms and had composed an oratorio (Jonah) that shares its theme with Michael's own most popular composition may reveal a symbiotic element to their friendship. Or it may all be just a happy restrospective coincidence.

|

Lennox Berkeley

© unknown

|

ROYAL MARINES SCHOOL OF MUSIC, DEAL

After Oxford, in the summer of 1953, a working life beckoned. Michael had applied for and, possibly to his surprise, was employed in the only full time paid work he ever undertook, as Professor of Composition at the Royal Marines School of Music, then located at Deal in Kent.

Michael's former tutor, Bernard Rose, wrote from Queens College. " My dear Professor ! How lowly this splendid title makes me feel. I can't imagine you in that job at all, but I am sure it will do you no harm, for a while anyway. "

"For a while anyway" turned into six years. Michael's predecessor in the post was his near contemporary Kenneth Leighton, who had also studied with Rose and had now taken a fellowship at Leeds University, and there is a sense that the newly-appointed staff member felt ill-equipped for the role by comparison. Certainly his homespun keyboard technique and an awareness of his less than accomplished ability to play from orchestral scores may have been a source of unease. |

| * awaiting illustration |

However he felt professionally about the appointment, Michael settled happily in new surroundings, renting rooms on the front at Walmer, namely Number 12 The Beach. Out of courtesy he had written to Leighton, who by reply agreed that the surroundings in Deal were pleasant ("I envy you the beach") but that the post should be regarded very much as a stepping stone. There are suggestions that, while Michael was scrupulous in carrying out his duties at Deal, the daily grind of working as a teacher, albeit in genial surroundings, was keeping him away from what he clearly regarded as his primary roles - to compose and write about music. It is illuminating to note that, after six years of being exposed to and working with brass and wind band music, there are only six pieces in this genre in Michael's oeuvre. But he was a popular instructor. |

Writing on the Royal Marines Band web forum, former pupil Thomas Lambert reflects: I was among the first of his pupils and I was lucky enough to get to know him really well. His soft, gentle manner coupled with a bright, acerbic wit, soon endeared him to all the members of his various classes.

There would not be one man in any of them who could find a criticism of his teaching technique, always a kind word of encouragement for those that found the mysteries of the �passing six four� in the same class as the Theory of Relativity.

|

|

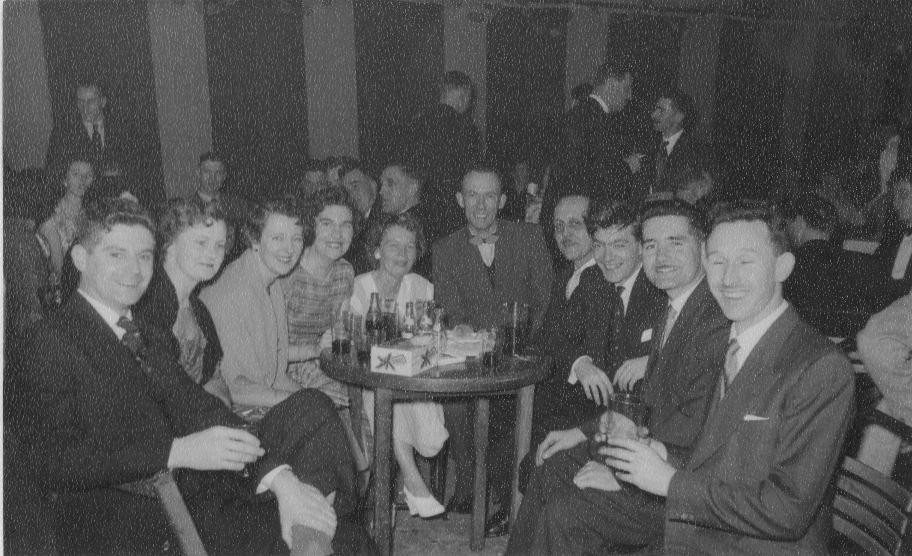

With members of the Band |

Lambert continues: For the �bright� and the �not so bright� student he was patience personified and could be relied upon to show, by musical example, how something could be made more acceptable than the student�s original.

|

All the time in Deal he was continuing his private studies with Lennox Berkeley and finding space for his own work. He also received occasional help from the Australian composer Arthur Benjamin, then teaching at the Royal College.

1954 saw work on an abandoned Concertino for clarinet and strings, together with correspondence with playwright Frederick Witney with a view to adapting Nuit de Noces as a chamber opera. This last finally made its appearance in 1998 as The Night of the Wedding.

|

In March of 1955 Michael was considering whether to apply for a job with the British Council, which was looking for someone to supervise music libraries in various overseas locations. A friend at the Council couldn't see any snags in the post, except for a very limited budget and the usual frustrations of issuing and keeping a watchful eye on the whereabouts of orchestral parts - a perennial librarian's lot. But there were shortly to be major changes in his circumstances.

His father Ted Hurd died at home in Gloucester on 15 September 1955, aged 78 and when Amy Hurd died on 30 November 1957 his share of the ensuing combined legacies enabled Michael to focus more securely on his ambitions to become wholly freelance.

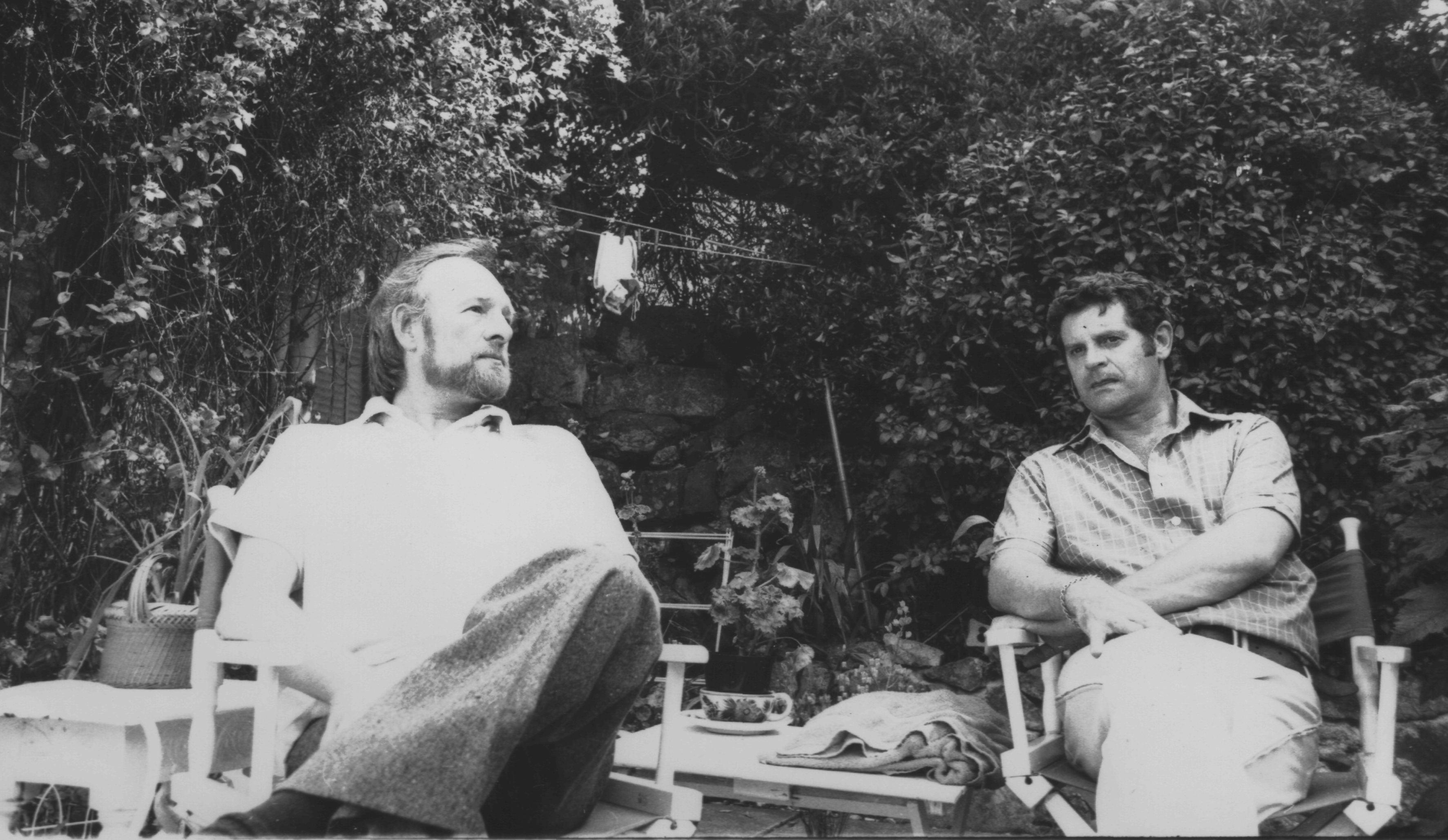

The other major shift came in 1959 when Rutland Boughton, with whom Michael had kept a constant and amicable contact, agreed that work on a biography was possible. Clearly such an undertaking would be difficult while shuttling between Deal and deepest Gloucestershire but David Hughes (who had married the actress Mai Zetterling in 1958) helped to sway Michael's subsequent decision by pointing out that he only had one life in which to do what he wanted to do. Hughes had settled with his new wife at Berry Grove, a rambling and comfortable former vicarage in West Liss, Hampshire. Michael was a frequent and welcome visitor at this time. |

Presentation on leaving RMSM Deal, 1959

|

Taking the plunge, Michael resigned from Deal in 1959, coincidentally ending his private studies with Lennox Berkeley, but not the friendship. Despite professional reservations, Michael enjoyed the personal aspects of his time at Deal and the esteem in which he was held is reflected in frequent correspondence from former bandsmen and colleagues. It was a considerable matter of sadness for Michael when a later burglar made away with his leaving gift of a silver coffee service. Research, conversations and writing for the Boughton biography continued apace, taking its title Immortal Hour from the senior composer's most famous work. The timing was all, as he later acknowledged, since Boughton died in January of 1960. Michael then moved to Hampshire, the final chapters of the book being undertaken while living at Berry Grove. As for his own compositions, they were restricted at this time to some song drafts and a handful of fairly conventional church anthems - perhaps still looking for his own true voice musically. |

1960s - IMMORTAL HOUR & JONAH-MAN JAZZ

|

Some days around this time were spent exploring the Stroud area of Gloucestershire with a view to settling in a suitable property, but working and living in Hampshire with the Hugheses helped Michael to conclude that it was a more congenial and practical part of the country in which to spend his time. The area around Petersfield was quiet but with an active musical scene and close enough to London to make work and research there a sensible prospect. For one thing, as he noted later, the extra-mural departments of both London and Southampton Universities overlapped, providing plenty of outlets as an adult education lecturer. Evidence of his methodical and practical approach to his chosen career rests in a small notebook of the time, in which he lists the local schools, choral and orchestral organisations - a thorough survey of potential (and as it turned out, actual) markets for his work.

|

Michael Hurd at West Liss 1962 (G Peck) |

Mind made up to settle, he began exploring properties and in the early summer of 1961, prompted by Hughes as to its availability, paid �1,500 for the terraced two bedroom cottage at 4 Church Street, West Liss that was to be home for the rest of his life.

Not five minute's walk from Berry Grove, Church Street suited Michael's needs admirably. Although by no means spacious, there was eventually room for three pianos and an extensive library. The galley kitchen, though compact, was sufficient to give the genial host full rein to conjure meals and a steady succession of friends and acquaintances enjoyed convivial Hampshire weekends over the years.

Visitors from those early times include Lennox and Freda Berkeley, Joseph and Jean Cooper, John Miller, Alan Rawsthorne, Howard Ferguson, Joy (Boughton) and Christopher Ede, Richard Rodney Bennett and Noel Coward.

|

Immortal Hour was published in 1962. Details of the writing of Michael's first biography of Boughton are outlined in the revised edition of 1993 (qv) but the author happily and gratefully acknowledges the support and assistance of Peter Price at Tibberton (only six or so miles from Boughton's home at Kilcot) while the work was in progress.

The publication of Immortal Hour achieved three purposes. It served as a tribute to a friend and fellow musician and it began a revival of interest in the life and work of a neglected English composer. Perhaps most importantly it proved that Michael Hurd could write, critically and thoroughly, about music and musicians. As a calling card for future projects, the volume would prove more than worth the considerable effort expended. More.

|

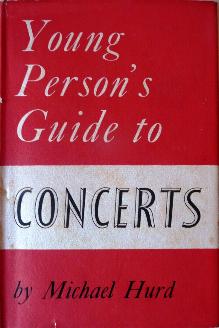

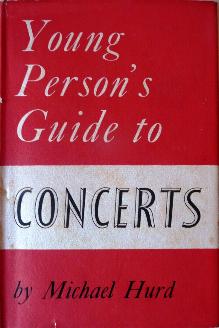

Having established his credentials with a publisher (Routledge & Kegan Paul) and reading public, the same year saw the first of three concise yet practical guides to general aspects of music, aimed at younger readers. The Young Person's Guide to Concerts is uncompromisingly serious, yet written with an admirable clarity that was welcomed by many librarians and school music teachers alike. More.

The further volumes, on Opera (1963) qv and English Music (1965) qv were equally successful and helped to establish the author in the minds of educators and music scholars as a name to be noted.

Another important and complementary strand in Michael's career began at about this time, with contributions to BBC radio's serious music service, the Third Programme (later Radio 3). A talk on William Walton for Adventures in Music was among the first of a long series of broadcasts, mostly on aspects of British music, delivered over the next forty years. |

"Mr Hurd provides the apprentice concert-goer with a very pithy background to the concert world, which will engage his intelligence quite considerably." Times Educational Supplement, 1962

|

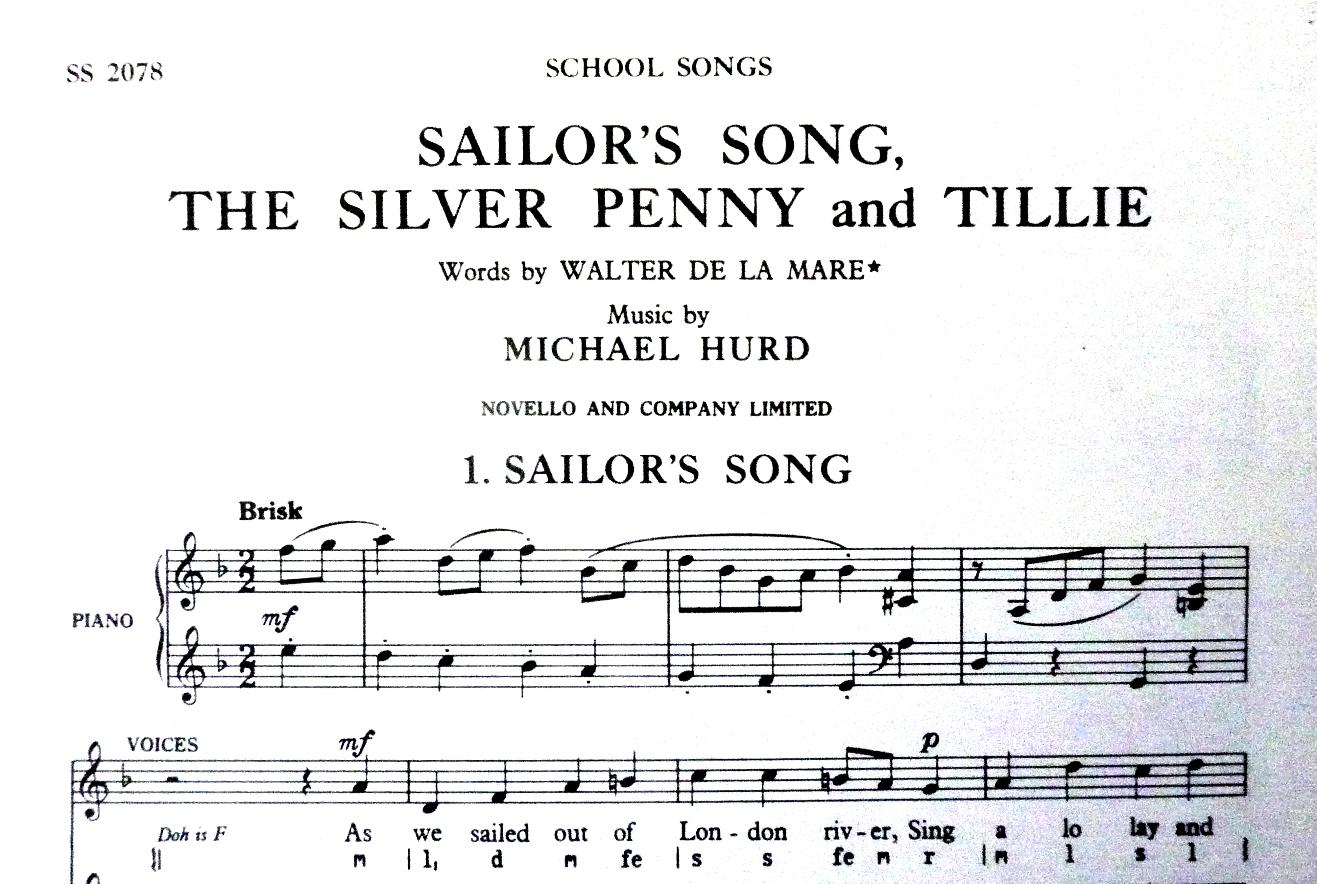

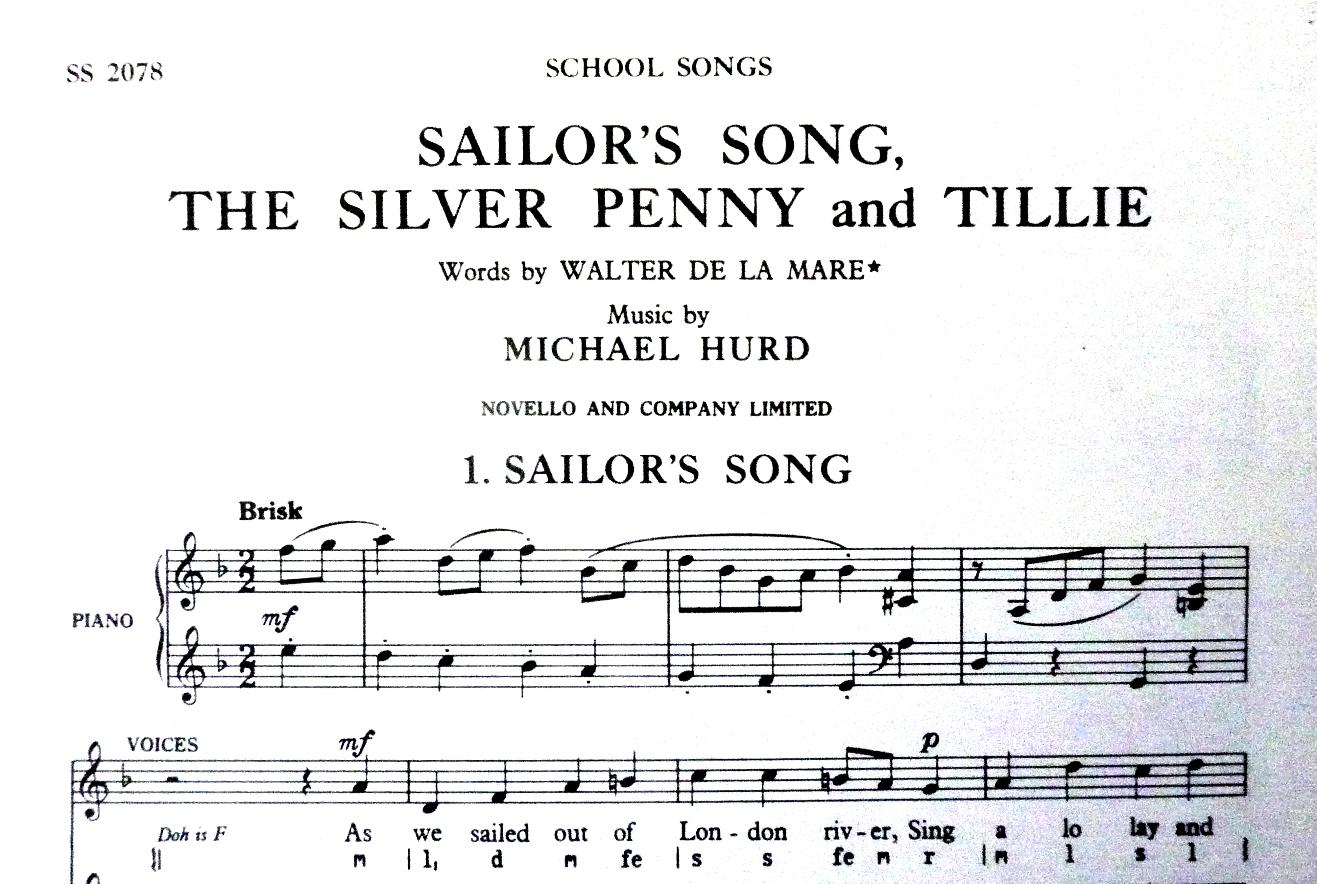

The first music in print

"Sailor's Song", "The Silver Penny" and "Tillie"

words by Walter de la Mare |

Finally, in the autumn of 1963, Michael achieved what must surely be one of every serious composer's ambitions - his work was accepted by a publisher. This was and remains by no means a simple process, as he himself remembered later:

" I had become accustomed to rejection slips, but having what it seemed to me to be a couple of practical unison songs, I decided to save time by sending them to three different publishers at the same time (Boosey and Hawkes, Curwen and Novello), confidently expecting that they would rebound with the usual rejection slip. Alas, within a week all three had accepted them ! Abject apologies to Boosey and Hawkes as well as Curwen, neither of whom were best pleased. But it was the beginning of a very happy and mutually beneficial relationship with Novello and Co. " |

1963 was proving to be a very busy year. In addition to the work already mentioned, Michael composed incidental music for his old school friend James Roose-Evans' stage version of Cider With Rosie at Kings Lynn and later in London; there were the Sea and Shore Songs (again from de la Mare) and music for Beverley Cross's The Singing Dolphin at the Hampstead Theatre Club.

|

|

Son et Lumiere (1962-4)

The late 1950s and early 1960s had seen a flourishing in Britain of son et lumiere productions in spectacular locations. Pageantry, lighting and crucially music and sound were employed in often quite elaborate presentations of local and national history. Christopher Ede, son-in-law to Rutland Boughton, was a noted producer of these complex events and of course known to Michael Hurd through the family. Both men were at this time serving on the committee of Adolph Borsdorf's 'Boughton Trust' - another benefit of Michael's pioneering work on Boughton - and it seemed a natural step for Ede to invite Michael to contribute incidental music for his productions. |

Beginning at Kenilworth Castle in 1962 and continuing through 1963 (Carrickfergus and Pembroke) to 1964 at Bury St Edmunds, these prestigious and highly successful commissions gave Michael his first real taste of composing for a large public audience.

From the outset Michael proved himself adept at delivering appropriate cues and themes, happy to let items fall should their use prove ephemeral once production work started, but also painstakingly specific in his demands and requirements. |

Very early in his career Michael had realised that, in his chosen world, making and maintaining friendships was essential. As a consequence much of his work came about through this sort of contact and, whereas the word "ruthless" might have been applied to him by some in this regard, this is surely a matter of context and perspective. After all, one does not generally look up composers in the yellow pages in the same way one might approach a plumber with a commission. Work has to be found - and paid for by someone.

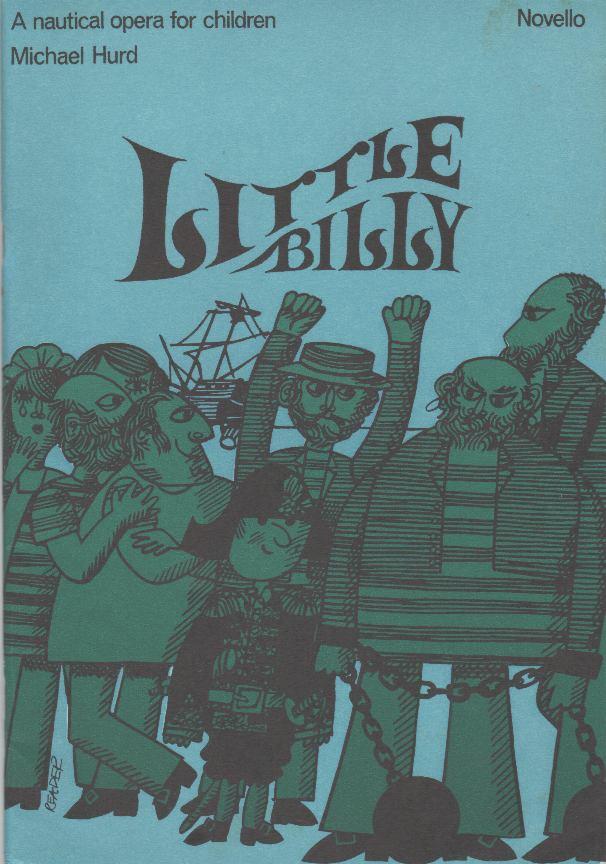

One example of what would now be called networking is Little Billy, his version of Thackeray's comic naval tale, which was written for Brightlands Prep School at Newnham on Severn in Gloucestershire. The master in charge of the production was his old school companion Geoffrey Peck, who has admitted that the piece was very ambitious for a small school with no real tradition of that sort of thing. Nevertheless the production was a success, the composer happy to return to his native county on the occasion of rehearsals and beyond. |

|

|

A sonatina for flute and piano was performed in Bristol in early 1964, which time also saw work on the Canticles of the Virgin Mary for Farnham Girls Grammar School. The artist John Miller, again a friend of some standing, was engaged to produce illustrations for Sailor's Songs and Shanties qv, published in 1965. The pair collaborated twice more, on a companion volume Soldier's Songs and Marches (1966) qv and the perennially successful Outline History of European Music (1968) qv. |

Jonah-Man Jazz (1966)  "anything that stays in the memory for

forty years with such pleasurable clarity

has to be a winner" ~ Nick Barnard

"a genre which must have introduced

a whole generation of children

to the pleasures of singing" ~ John Sheppard

|

Self-confessedly but rather archly referred to the result of a "mis-spent Christmas", the work for which Michael Hurd is perhaps best known in many circles is as near as perfect in form and execution as it could be. One correspondent to these pages, who took part in a performance about forty years ago, could remember practically every word and note. The composer's own test of a decent tune was to have just this effect (" If you can't remember your own tune overnight, how can you expect others to learn it easily ? "), so it scores well on that account.

At the time of composition, Michael had built a portfolio of musical activities in and around his adopted home county, which included regular and sympathetically pithy duties as a festival adjudicator. He came to the conclusion that, albeit he had written some similar pieces himself, conventional part-songs about flowers, empire-building or the seasons, drawn from traditional verses, may not be hitting the mark as far as engaging young performers and their teachers was concerned.

The resulting ten minutes of succinct entertainment proved an instant hit with its target performers and their audiences, and very much remains so today. As recently as November 2011 Jonah-Man Jazz was heard within the mock gothic splendour of Speaker's House in Westminster as part of a reception celebrating schools music in Newham - proof indeed of its longevity. Further details of the piece and recordings here.

|

The year of Jonah found Michael working well-settled into his routine of working and living in Hampshire. He had made the acquaintance of one Mrs Grant, a retired antique dealer who lived in the Old Rectory at West Liss. Friends from the village have described Michael's "playing for his supper" (actually Sunday lunch) at the rectory and beginning to indulge his passion for collecting antiques and curios. His own, rather eccentric collection was augmented when Mrs Grant died and a small parcel of land he also inherited was given to the local cricket club. | |

Part of an extensive collection of naval ephemera | A particular enthusiasm - some would say obsession - was with the navy of Nelson's era, and Michael eventually gathered up a substantial and valuable "naval museum" of his own: scrimshaw work, Sunderland ware, ships in bottles, prints of Nelson's funeral and the Trafalgar victory, sailors' shell valentines, prisoner of war ivory work, together with a considerable library of descriptive work and songs from the era. The Nelson theme in Michael's life and work came to a satisfactorily triumphant climax in 1975 with the publication of his "mock oratorio" Hip Hip Horatio qv. The composer also took a special interest in the life and career of Charles Dibdin, the naval propagandist and composer of "Tom Bowling", eventually acquiring a valuable collection of rare editions of his work. |

Petersfield Festival

In Michael's own words, " Genius can command anything but talent must be practical, modest and useful." With this in mind he developed extremely strong and productive links with the local music-making community. For example, 1966 saw the start of a long and mutually beneficial connection with the Petersfield Festival in Hampshire, beginning with his work as a competition adjudicator. Two years later he became music advisor for the youth day and, feeling a strong need to revitalise and modernise the event, set about this work with his usual and highly effective mixture of charm, robust opinion and energy. A full appreciation of his work for the Festival can be found here. |

Petersfield Festival Hall |

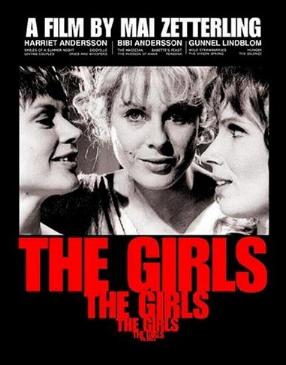

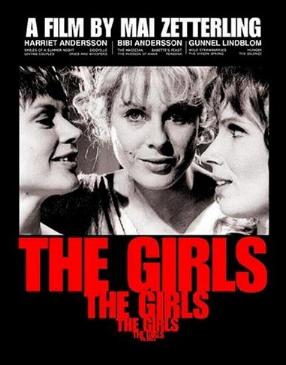

Michael's continued and strengthening friendship with David Hughes and Mai Zetterling took his work into a new direction at around this period. In early 1968 the pair had adapted Lysistrata, the drama of sexual politics by Aristophanes, for the cinema, with the title Flickorna, aka The Girls. The challenge of providing a score for the movie, albeit a very spare and concise one, was one that Michael readily accepted. Reportedly the crew were quickly whistling the main theme on the set, superstitious tradition maintaining this as a sure sign of success in this medium.

Michael's continued and strengthening friendship with David Hughes and Mai Zetterling took his work into a new direction at around this period. In early 1968 the pair had adapted Lysistrata, the drama of sexual politics by Aristophanes, for the cinema, with the title Flickorna, aka The Girls. The challenge of providing a score for the movie, albeit a very spare and concise one, was one that Michael readily accepted. Reportedly the crew were quickly whistling the main theme on the set, superstitious tradition maintaining this as a sure sign of success in this medium.

Promoting the finished film involved a great deal of foreign travel for the co-scriptwriters - Cannes, Venice and Los Angeles - leaving the composer as virtual caretaker of their Hampshire home. The ensuing correspondence, invariably typed in Hughes' entertaining and mildly wistful style, carries frequent references to milkman's bills, leaking roofs, elusive insurance documents and other domestic ephemera. But it paints a picture of a comfortable and trusting co-existence. Support for and interest in Michael's own work was never far away from this quarter. There were further film score commissions from Zetterling in 1982 (Scrubbers) and 1990 (Sunday Pursuit).

|

1980s

One commission at the turn of the decade brought Michael back to a key place in his personal and musical development. Mai Zetterling was to direct a new play by the American experimental dramatist William Saroyan. It would be staged at the English Theatre in Vienna and would Michael like to write the incidental music ?

|

Michael in Vienna once more, 1980 |

Play Things comprised a sequence of scenes in which everyday objects, such as a stuffed tiger or a cup and saucer, take life to argue a variety of themes and paradoxes. The striking design was by Andy Warhol and this fact, together with the general theme, makes the whole venture the very nearest Michael ever got to being involved with any aspect of the avant garde.

Although the play was considered to be only a minor success, Saroyan was pleased with all details of the production and in any case, the experience gave Michael an excuse to revisit some favourite haunts. There was also the bonus of working once more with an old and staunch ally. Saroyan was asked to write another work for the English Theatre, with the same director and composer, but for reasons lost to time the project was never followed through.

|

On an incidental and personal note, Mai Zetterling had been divorced from David Hughes the previous year. Michael was invited to Hughes' subsequent wedding to Elizabeth Westoll in November 1980. In a continuing voluminous correspondence throughout this period there is however no suggestion that Michael's friendship with either of his friends was in any way affected by their own changing circumstances. |

In 1984 Michael found himself in Australia on a tour of promotional and educational work. Interviewed in that country for a radio broadcast, he explained the origins and nature of his visit, but the conversation expanded into a wider-ranging exploration of his working life and musical philosophy.

| The interview (20 mins or so) can be heard in MP3 format by clicking this link |

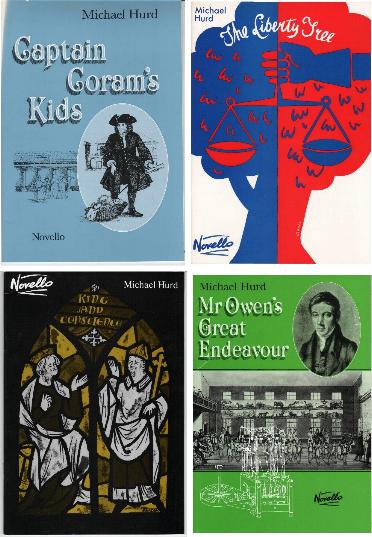

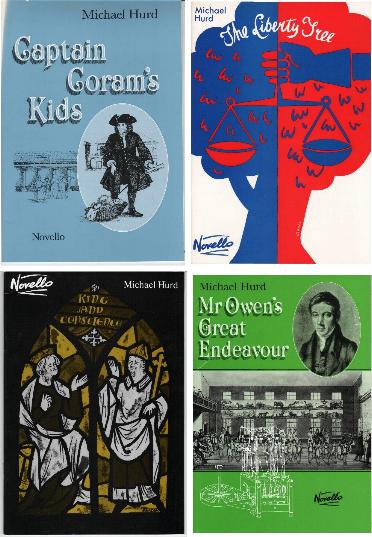

1987 saw the commissioning of four major works for young performers by the Heritage Education Trust. Captain Coram's Kids, a ballad cantata on the theme of the Coram Foundling Hospital in London, received its first performance in the Banqueting Hall, Whitehall on 12th November 1987.

This was followed by The Liberty Tree (1989), taking its subject from the English Civil War and King and Conscience (1990), which explored the story of Henry II and Thomas à Becket. The quartet was completed with Mr Owen's Great Endeavour (1991), on the socialist philanthropy of mill-owner Robert Owen, premiered appropriately enough at New Lanark in Scotland.

The ballad cantata style of narrator, chorus and simple yet clear exposition of quite complex historical material was an admirable vehicle for Michael Hurd's skill at both word setting and concise control of accessible yet challenging musical forms.

|

|

1990-2006

|

|

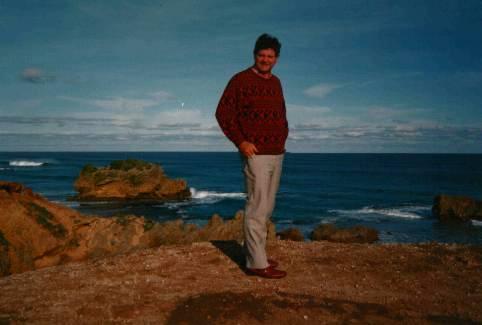

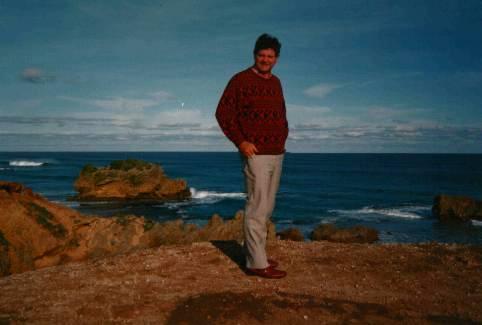

Port Fairy Spring Festival, Australia

Michael Easton

|

In 1989, while on a promotional tour in Australia, Michael was invited by his friend Michael Easton to visit his new home on the coast at Port Fairy, near Melbourne. The location and spirit of place reminded him of Aldeburgh and its attendant festival established by Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears. Perhaps something similar could be attempted here? There was a church, a hall and a convivial community atmosphere. He put the thought to Michael Easton and Len Vorster over the weekend of 22 July, it was well received, and a festival was born. |

The first festival weekend took place in 1990, which Michael was unable to attend due to commitments in England, but he was able to be present at future occasions, giving pre-concert talks and devising entertainments. One such affair was entitled The Mozart Question, with Michael appearing as The Judge. More significant were performances of his own music. The Day's Alarm, a setting of some intense verses by Paul Dehn, received its premiere at Port Fairy in 1991 and The Widow of Ephesus was produced in 1993. Composer John McCabe (composer, performer and frequent Festival visitor,) described the chamber opera as "very entertaining and skilful". In 1995 the Festival commissioned The Aspern Papers, Michael's three-act opera from the Henry James novella, of which further details here. In Michael's own words, "They gave it a wonderful production, much better than anything I could have expected in England."

|

Michael on the Australian coast

|

Len Vorster & Michael Smallwood

premiere Carmina Amoris, 1998 |

It is clear from his own notes and from recorded contributions that Michael felt very drawn to the Australian climate (both actual and artistic) as well as the friendships developed over many visits. Michael Easton was Novello's representative in the region and cunningly arranged several lecture and teaching tours for Michael. There is more than one suggestion that, had the opportunity presented itself in earlier times, Michael might very well have settled Down Under and his notes about the idea carry a rare tone of regret. A cause of real sorrow at this time was the death of Mai Zetterling from cancer in March 1994. Michael's close friendships were few but deeply held and the absence of one of his earliest and most effusive supporters was keenly felt.

|

Shakespeare at Tibberton Court (1995, 1998, 2001)

In the spring of 1995 Gordon Fluck, with whom Michael had worked on The Widow of Ephesus and other projects, invited the composer to contribute incidental music for a production of Romeo and Juliet. Michael readily agreed, not least because the play was to be produced against the backdrop of Tibberton Court, near Gloucester. Formerly where the late Peter Price had an apartment, this had been the base for Michael's research into and writing about the life of Rutland Boughton. He also served for a time on the board which administered the estate, until distance and less confidence about driving intervened. About this time he had also suffered a distressing burglary, which made him understandably rather reluctant to spend more time away from home than was strictly necessary.

|

Tibberton Court |

Dawn Hemmings & Simon Cove

© Jack Farley, Gloucester

With a quasi-renaissance setting and design, Michael met his brief with telling effect, especially in the dance sequences for the Capulets' ball and Juliet's funeral procession. Melodically modern but harmonically authentic, the contribution of the music to the atmosphere of the event was sustained and highly effective.

The presentation of the music was technically tantalising for Michael, since the score was arranged and realised using a computer. Pronouncing himself "far too old" to get to grips with such wonders, he was nonetheless delighted and fascinated by both the process and the results. The August production was part of the Three Choirs Festival fringe events for that year and coincided with the launch of the Ivor Gurney Society.

| |

Such was the success of Romeo and Juliet, further similar ventures were mounted in 1998 (Comedy of Errors) and 2001 (Much Ado About Nothing). It is probably fair to note that by the time 2001 arrived Michael felt that he had written all he wanted to write in terms of music. But, as ever, he produced material of high quality to a deadline and for a minimal fee, mindful of both professional and personal standards, a pattern throughout much of his working life. |

|

Michael's seventieth birthday in 1998 was celebrated quietly with friends but an earlier public acknowledgement gave him great personal satisfaction. The Three Choirs Festival featured Shore Leave in an afternoon concert on 19th August, Denise Ham conducting the Cheltenham Chamber Orchestra with Roderick Williams as soloist.

With pleasing synchronicity the other items in the programme were by Parry, Finzi and Gurney - fitting company for one of the signature works of a composer who had for so long championed and celebrated English music.

Michael's note to the soloist refers to the latter as "being lumbered" with the piece, but then goes on to suggest very detailed notes about the performance. It serves to underline the impression of a serious and painstaking composer who affected to be surprised and amused by his own success.

|

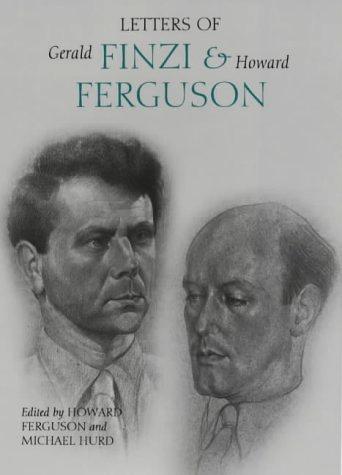

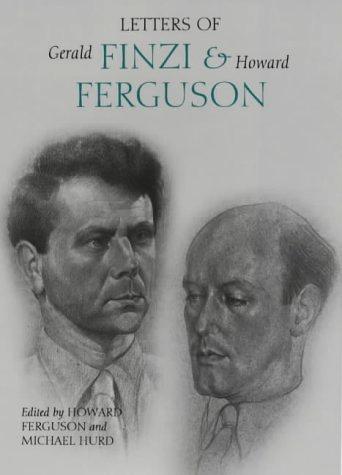

| As the decade drew to a close, Michael was fully engaged in what was to prove his final literary work. His long-standing friendship with Howard Ferguson had led to his being drafted in to complete the background sections of an edition of Ferguson's correspondence with Gerald Finzi. A friend relates that, devoted to this project, Michael expressed hopes that he would be able to see it through. This does not seem to have been particularly for reasons of impending mortality, but simply an acknowledgement of the size of the task involved. It was with great satisfaction then that in October 1999 Michael was able to travel to Cambridge for Ferguson's ninety-first birthday celebrations on the 21st. With him he took the complete manuscript of the edition. In a curious echo of his earlier work with Rutland Boughton, who died shortly after Michael completed his major personal research for the biography, this was timely. Ferguson died in his sleep on 1st November. Letters of Gerald Finzi and Howard Ferguson was published in 2001 to a gratifying critical reception, but the completion of what he regarded as a personal obligation gave Michael a deeper, albeit modestly expressed sense of achievement.

|

As happens with the passing of years, further personal sadnesses began to cloud the scene. John Miller, who illustrated three of Michael's early books, died in 2002. Michael Easton's death in 2004, at the tragically early age of 49, moved Michael very deeply - as did the passing of his old friend and ally David Hughes the following year.

|

CODA |

|

Michael Hurd was diagnosed with cancer in early 2005. In common with many details of his private life this news was kept to a very small circle of friends and immediate neighbours in Hampshire, the latter providing invaluable support and kindnesses. |

Michael died in Petersfield Hospital on 8 August 2006. His funeral at Chichester crematorium on 22 August was a splendidly-attended occasion of music, celebration and laughter. Among the music played was the central andante movement of the Sinfonia Concertante. |

|

|

His ashes were interred in the churchyard at West Liss on Saturday 20 January 2007, within sight of his home for over forty-five years. The private, non-denominational ceremony was followed by champagne and smoked salmon canapés, a mild extravagance with which he would have thoroughly approved.

|

The Petersfield Music Festival dedicated their opening concert of the 2007 season, on March 9th, to Michael's memory. His music manuscripts were deposited in the Bodleian Library, Oxford; his conductor's batons were presented to Petersfield Festival by his executors and after some other private bequests the residue of his estate was gifted to the Performing Rights Society and the British Music Society. Details of the trust established by the BMS with this bequest can be found here. The main purpose of the fund is to promote commercial recordings of Michael's music, a process that is in full train at the time of writing.

|

|

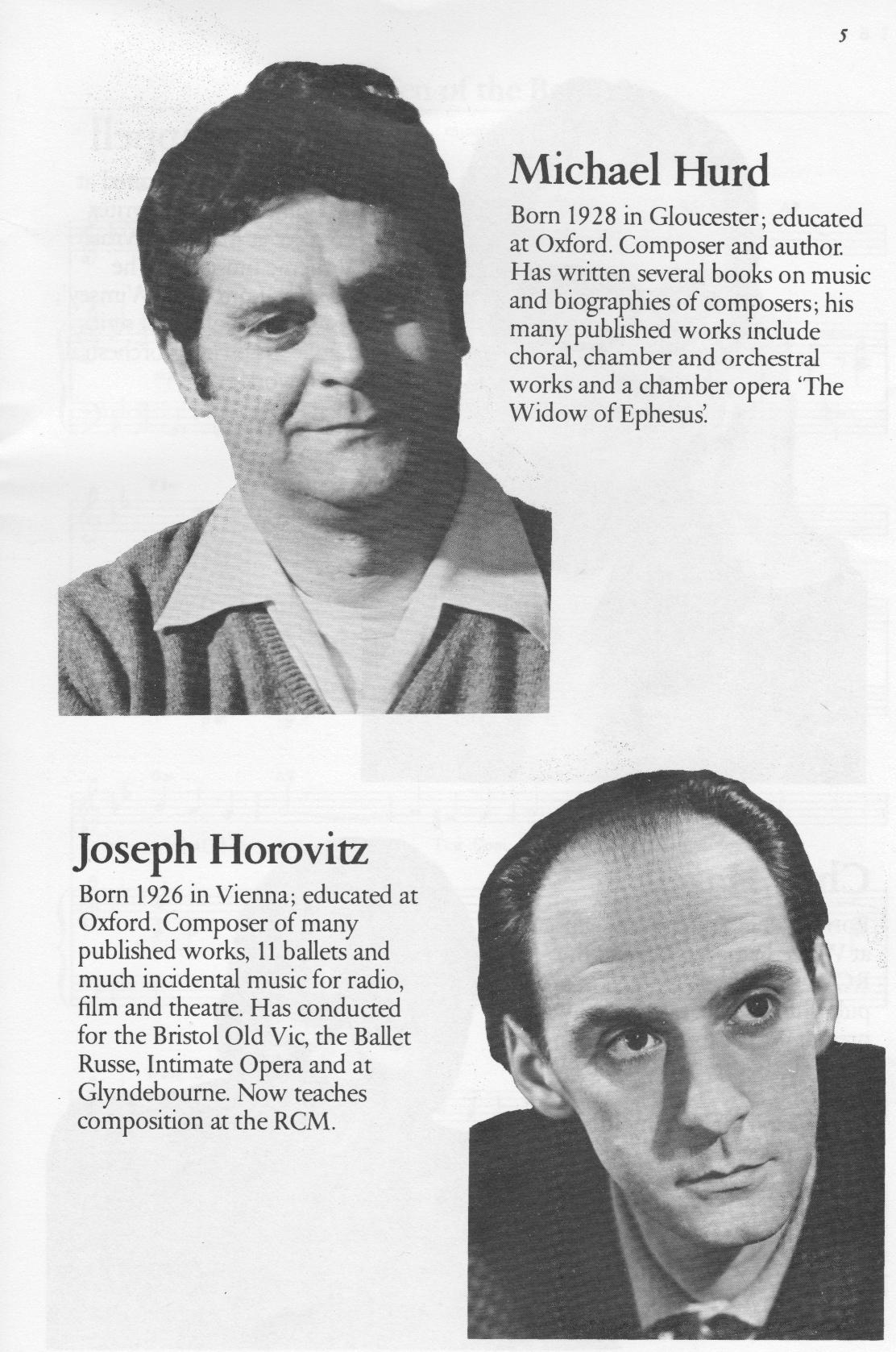

MICHAEL HURDComposer and Author

1928 - 2006Michael Hurd is survived by his music,

his published writing and those fortunate

to be numbered among his friends.

|

|

Despite the post-war privations still holding sway, as strikingly depicted in the film The Third Man, that most romantic city's cafes, bookshops, theatres and above all the opera provided just as valuable an education as the deferred entry into Oxford University. The duties with the Intelligence corps were in connection with the chaos of the refugee problem but Michael's role involved little more than clerical work. Whatever the tasks assigned or his attitude to them, he played the game enough to end his time in the army at the relatively lofty rank of sergeant.

Despite the post-war privations still holding sway, as strikingly depicted in the film The Third Man, that most romantic city's cafes, bookshops, theatres and above all the opera provided just as valuable an education as the deferred entry into Oxford University. The duties with the Intelligence corps were in connection with the chaos of the refugee problem but Michael's role involved little more than clerical work. Whatever the tasks assigned or his attitude to them, he played the game enough to end his time in the army at the relatively lofty rank of sergeant. Determined, however, to enjoy life to the full and falling in with a like-minded coterie, the twenty-year old flourished in Vienna, living as he did in apartment in the city rather than some remote barrack block. He returned as many did to civilian life with a markedly increased maturity in experience and outlook - which was, of course, a major aim of the whole National Service exercise.

Determined, however, to enjoy life to the full and falling in with a like-minded coterie, the twenty-year old flourished in Vienna, living as he did in apartment in the city rather than some remote barrack block. He returned as many did to civilian life with a markedly increased maturity in experience and outlook - which was, of course, a major aim of the whole National Service exercise.

Having deferred his entry to Oxford until the Michaelmas term of 1950, Michael had a year to fill, which he did partly by occupying a menial clerical role in the RAF Records department in Eastern Avenue, Gloucester - again, just a short walk from home. There were already school and other acquaintances up at the university, and some free time was spent there and in London, but he continued his self-education in the realms of music and literature. A friend from those days notes a slight withdrawing at this period, as if the young man was becoming more focussed on what was to become his career.

Having deferred his entry to Oxford until the Michaelmas term of 1950, Michael had a year to fill, which he did partly by occupying a menial clerical role in the RAF Records department in Eastern Avenue, Gloucester - again, just a short walk from home. There were already school and other acquaintances up at the university, and some free time was spent there and in London, but he continued his self-education in the realms of music and literature. A friend from those days notes a slight withdrawing at this period, as if the young man was becoming more focussed on what was to become his career.

Michael's continued and strengthening friendship with David Hughes and Mai Zetterling took his work into a new direction at around this period. In early 1968 the pair had adapted Lysistrata, the drama of sexual politics by Aristophanes, for the cinema, with the title Flickorna, aka The Girls. The challenge of providing a score for the movie, albeit a very spare and concise one, was one that Michael readily accepted. Reportedly the crew were quickly whistling the main theme on the set, superstitious tradition maintaining this as a sure sign of success in this medium.

Michael's continued and strengthening friendship with David Hughes and Mai Zetterling took his work into a new direction at around this period. In early 1968 the pair had adapted Lysistrata, the drama of sexual politics by Aristophanes, for the cinema, with the title Flickorna, aka The Girls. The challenge of providing a score for the movie, albeit a very spare and concise one, was one that Michael readily accepted. Reportedly the crew were quickly whistling the main theme on the set, superstitious tradition maintaining this as a sure sign of success in this medium.

A high point was reached in 1978 when Novello issued a score sampler of pop cantatas from their stable, Ten of the Best.

A high point was reached in 1978 when Novello issued a score sampler of pop cantatas from their stable, Ten of the Best.